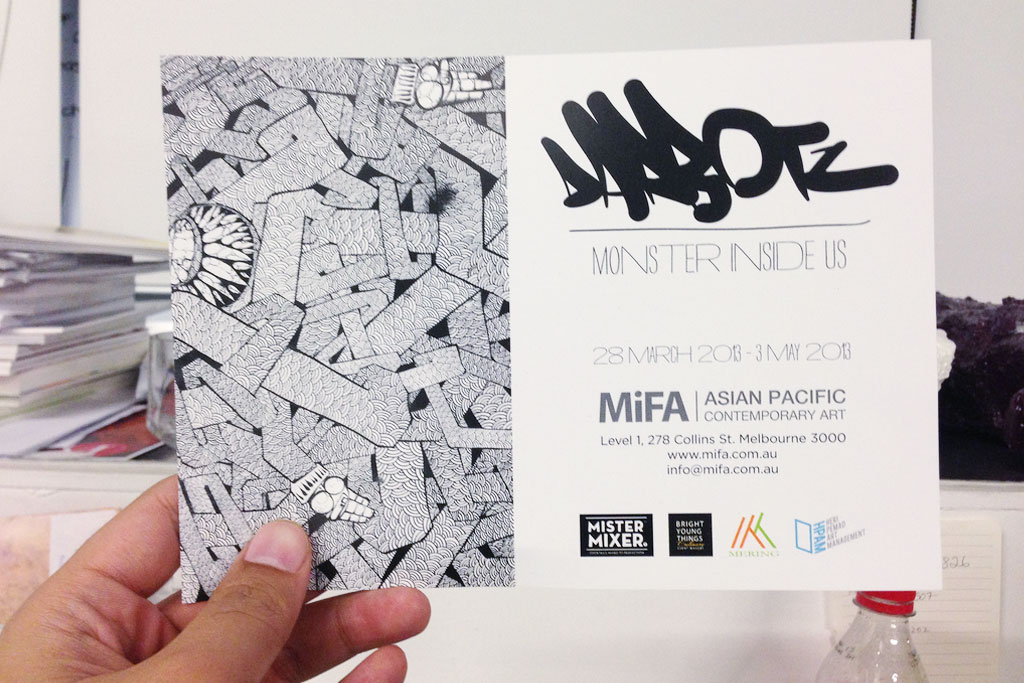

Galleries and Graffiti with Darbotz

Ken Jenie (K) talks to Darbotz (D) as he exhibits his work in MiFA

by Ken Jenie

K

How did you first gain interest in the arts?

D

I think everybody loves to draw when they were kids. I remember I loved all those Japanese robots. So I can say I’ve loved arts since I was a kid.

K

Can you share a little bit about your background? Did you have formal training in the arts?

D

Not really. Actually, I studied visual and communication design. I learned art by doing it on my own.

K

What are some of the art and artists that influenced the development of your work?

D

I always love what KAWS has done. He uses all kinds of symbols and icons, he also uses all kinds of materials and projects.

I love Os Gemeos too, they took graffiti/street art to the next level.

K

How did you first begin developing your work; particularly graffiti? Has street art always been the format you wanted to work with?

D

Oh yeah, I have always loved the streets. I love the vibe and the adrenaline rush. After doing some drawings on paper, I wanted a new medium to explore, that’s why I started drawing on walls. I like to explore all kinds of mediums, but the wall is my favorite.

K

How did you begin doing graffiti?

D

Like I said before, I’ve always loved the streets. I began tagging my high school gang’s insignia back in 97’s; that’s where I learned about hand style graffiti tagging. In college my interest became more focused when I began discovering more street art. I began to use stencils, paste-up, etc. Then in about 2003 I began to make the squid character, but it did not look the way you see it today. The character has evolved – it used to be colorful. Back in university I studied a theory called semiotic. Conventional graffiti is writing your name, what I’m trying to do is make my work known without writing my name. It’s like how advertising works. From then on I began to mix graffiti and street art.

K

There has always been a discussion regarding graffiti as a form of expression and as vandalism. As graffiti is becoming more and more recognized by institutions such as galleries and even commercial institutions, what is the world’s view on graffiti now?

D

Graffiti is the streets, it has to be on the streets. Once you go to a gallery you become an artist. It will always be a controversial issue.

K

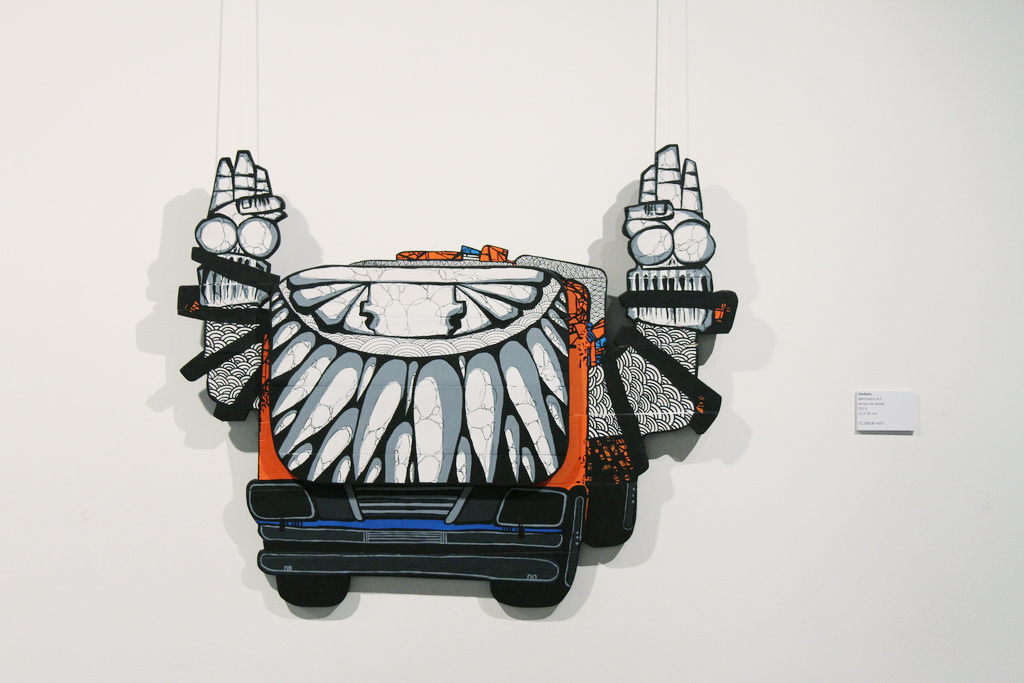

What are the themes that you address in your work?

D

My work is pretty much about my city. You can say it is how I feel about the city of Jakarta, a feeling I believe other people feel about Jakarta and other big cities.

K

Is there a goal that you would like to reach as Darbotz?

D

I want people to remember me for the next 100 years.

K

Can you tell us about your approach to your work? What is your process when creating art?

D

I think it’s very simple. When I do graffiti on the street, I sometimes scout the spot that I want to hit, sometimes I plan and sketch, and other times it’s just freestyle. When I work with canvas or any other medium, planning and sketching is very important. First thing is the message that I want to express. Art like these are a bit different – some people really want to know what it is about.

K

You have worked with companies such as Nike and JanSport in creating custom products. How do you approach these projects? Are there limitations when working with commercial entities?

D

I do all of this because it’s my passion, and along the way people notice my work. I honestly won’t take a project if they do not give me freedom. So basically all of these companies want to work with me because of what I have done.

K

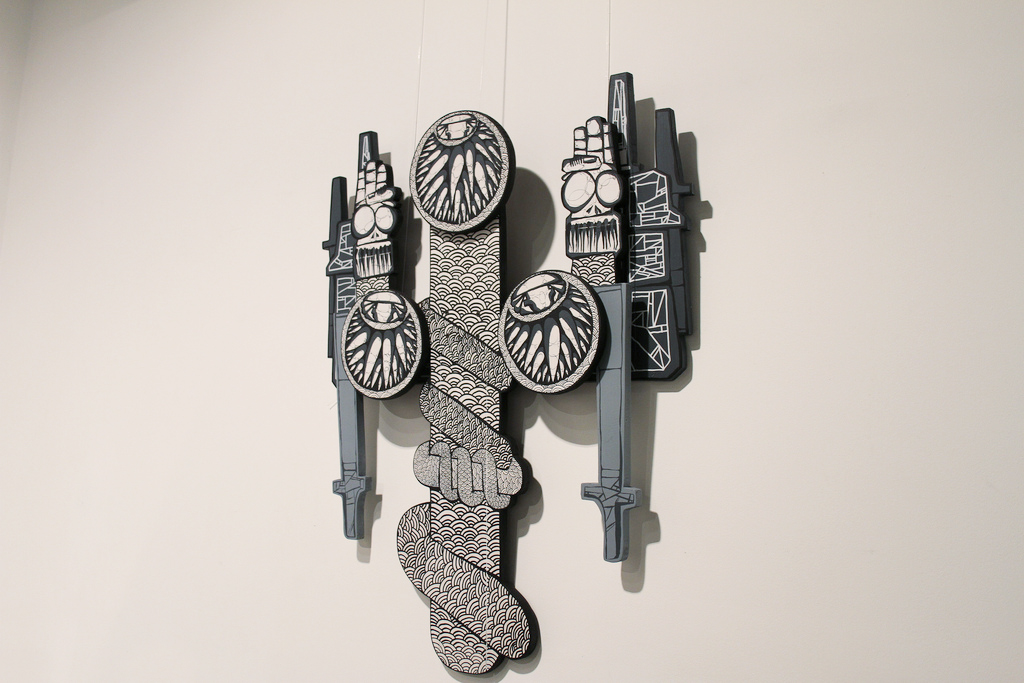

The characters you created has become synonymous with Darbotz. How did you develop the characters you use in your art? What do these characters represent (if at all)?

D

It’s my alter ego. If you see it carefully it’s me wearing the hoodie, its like Kenny from South Park! The characters is me facing the city everyday.

K

How did black and white become your dominant colorway? Did your use of monochrome happen naturally or was it planned?

D

It was planned. I used to use colors before, but I wanted my work to standout. There are too many colors on the street, that’s why I use basic colors – black and white – to neutralize them all. I can always add some colors to get some accents along the way.

K

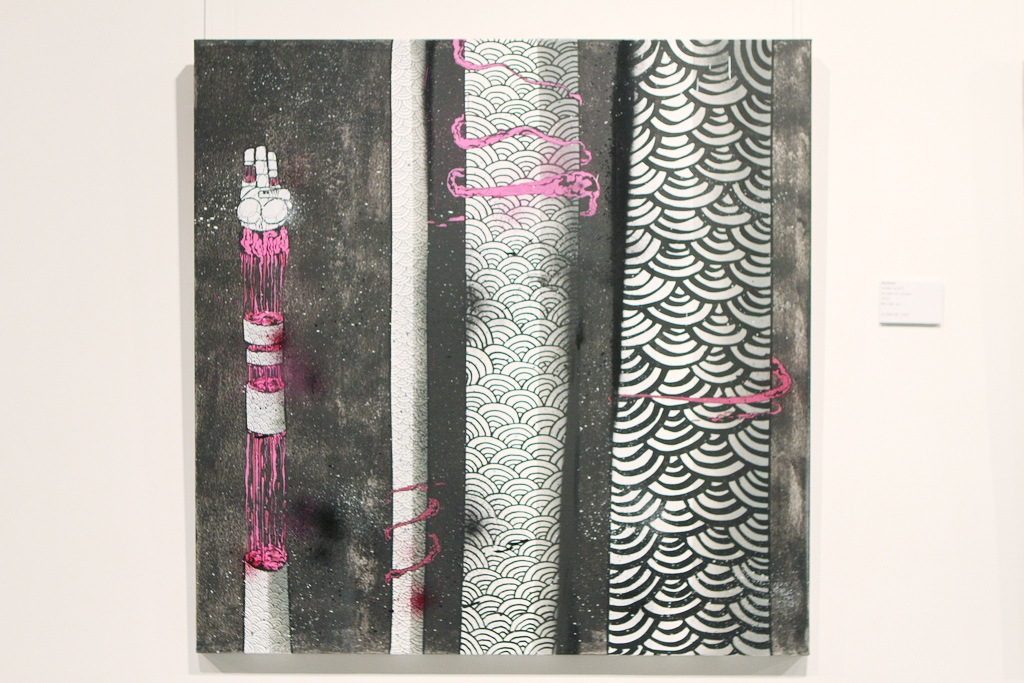

You have had your work displayed in galleries, including your recent work in Melbourne Intercultural Fine Art (MiFA). How does street art translate in this environment? Do you use a different approach for different environments in displaying your work?

D

Like I said before, street art was meant to be on the street. Once you go to a gallery, you become an artist, but with “street” vibe to your work.

It is difficult to transition street work to a gallery, but I always love contradiction. Galleries are pretty much sterile environments; I love figuring out how to make them look like the streets that’s why my work looks dirty, rough, raw. It is like what you see on the street.

K

Do the visitors react differently from when they see your work on the street? How so?

D

Pretty, much yeah. Some do not agree with putting street art in a gallery, some love it. But yeah, I’m a street artist and I’m still doing it. I don’t just steal “street” culture and do it in galleries like a lot of artists I see nowadays.

K

Is there, or should there be a distinction between having one’s work on the street and in a gallery?

D

They are just mediums. I use spray paint only when I do graffiti, but when it comes to galleries I can explore a lot of other mediums, which is fun. Don’t get stuck in one thing, you’ll get nowhere.

K

What has the response been like for your work abroad?

D

It has been pretty well appreciated. Don’t you love it when different types of people appreciate your work? From kids to institutions, from local street artists to gallery owners, or even a collector.

K

Having done a considerable amount of travelling, what is your observation of Indonesian art in comparison to what you have seen abroad?

D

One thing I can say is, we [Indonesia] are in the game. We are on the same level if we talk about the skill. We just need more exposure and appreciation, and we need to have our own distinct style, an Indonesian style.

K

You have mentioned in previous interviews that your art is a response to Jakarta. What are these urban elements in Jakarta that inspire your work?

D

Everything. Its traffic jam, its pollution, its chaos, its hecticness, its corruption, etc.

K

What is Jakarta, Indonesia for that matter, like for artists? Is it a conducive and supportive environment to create?

D

Oh yeah, every city is a good place to create art, and you can see the differences between cities. Yogyakarta is the place to be right now if you want to talk about Indonesian art, but other cities also have potential.

We just need more support from people and the artists to be more passionate about it. You can see all sorts of different styles from each city, like Yogyakarta, Bandung, Jakarta, etc.

K

What are your thoughts on Indonesian art? Is it a developing scene? What are the problems you see here?

D

A lot of foreigners see the Indonesian art movement, particularly in Yogyakarta, as a renaissance. Like I said other cities need the exposure too and sometimes it’s unfortunate to see people copy/bootleg other people’s work. I know its not only happening here in Indonesia. I know nothing is original anymore, but c’mon, we know what you did. In some case like street art, people really need to know what street art is and what graffiti is. Some think they know but they don’t.

K

What is next for Darbotz? What are you working on?

D

I have a couple of group exhibitions coming this year and more solo exhibitions. I’m also working on a commission to paint a whole hotel building. Let’s wait and see!

Photography by: Nadine Maulida (2-16), Blair Nolan (17), Abang8 (21 & 22), Vanderlism (19), & Darbotz (18 & 20)