Crossing Borders with Dave Lumenta

Athina Ibrahim (A) meets with Dave Lumenta (D)

A

What was your first traveling experience?

D

I was born in Amsterdam in the year 1971. From a very young age, I was already accustomed to traveling. Our family would travel to Belgium, France, and then traveling by ship to England. I remember Europe to be different from how it is now. It wasn’t EU (European Union) but still EEC (European Economic Community). The border control then was so visible and a single market didn’t apply yet. Other Europeans needed a passport to travel around European countries. And when we entered a supermarket, the commodities sold were so different in each country you are in. These differences between the countries were very contrasting.

So my first traveling experience did start from being in Amsterdam. The first time I saw Indonesia was in 1978 and I had to transit to a number of countries before Indonesia. There was a total of 5 stops made. I had to go to Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Rome, Jeddah, Bombay, Thailand, Singapore, before finally reaching Indonesia. What was striking to me back then was that differences were embraced. If you see airports now, every one of them looks the same; even candy shops has the same look. In the 70s, when you were in Bombay, the airports had no AC and the character of India as a country really stood out.

A

Could you say the striking differences in culture you understood early on was what influenced you to major in Anthropology?

D

Not directly. I always enjoyed reading Tin-tin when I was little. I was also immersed in geography from a very young age.

A

Can you tell us your background? Before you got into Anthropology?

D

Originally I took fine arts in ITB (Institut Teknik Bandung) for two years but realized I couldn’t go through it because I enjoyed playing music instead. So I returned to Jakarta in 1991 and took an entrance test to UI (Universitas Indonesia).

When I graduated from high school in 89, I actually was already accepted in the anthropology faculty in UI, but since I liked photography and drawing at the time I got accepted to fine arts in ITB. Eventually my hobby in photography was put aside because I was very much into music. I returned to Jakarta and got accepted again to the Anthropology major.

I didn’t know then what I would end up working as with an Anthropology major.

A

Do you think studying Anthropology is what gave you path to your travel exploration?

D

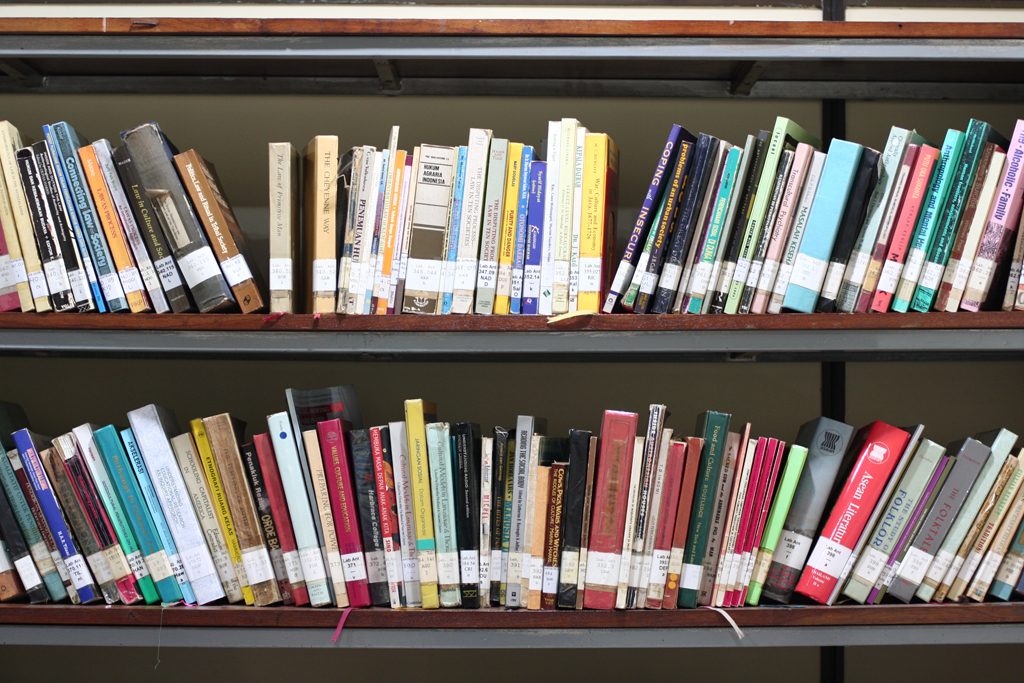

Anthropology gave me an interesting travel experience. It made be immersed in the type of traveling that made me understand my own grassroots. I would often travel around Indonesia — especially Java. But the travels wasn’t to seek exotic things, it was seeing a different side of Indonesia. As a student we were exposed to a different side of Jakarta by exploring the suburbs and slum areas, including areas as Rawa Bebek or Penjaringan. We made it a habit of noticing things that co-existed with us but are never given enough attention to.

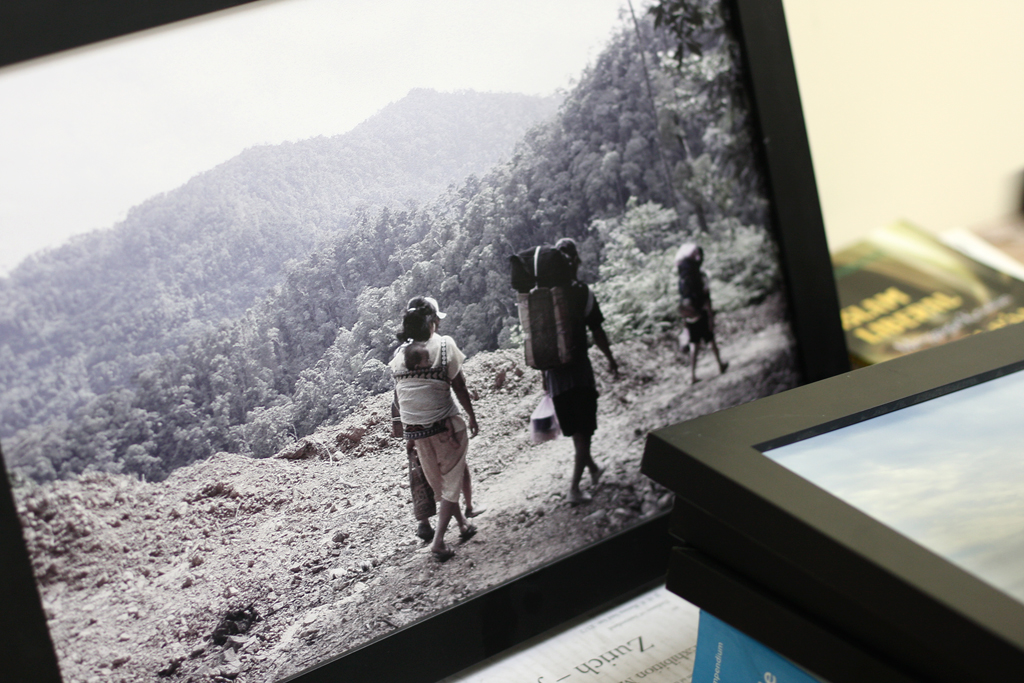

Part of the travel in studying anthropology is done for research. We would live with people and dig deeper to understand people and their culture. Only when I graduated did I truly had the chance to get out and explore on my own. In 1997, there was a large fire in Kalimantan Tengah and I joined a non-profit organization to be part of their social program. I also worked at the World Food Program to support villages in Indonesia.

Even though most of the travel was for research, I had the chance to intensively explore each area. My traveling itinerary were mostly focused in small villages. I don’t really travel to tourist destination to seek beautiful landscapes, that normally is the bonus to my travels but never the main purpose.

In the end, it’s the uncertainty that I am looking for.

A

Would you say these experiences of being in a different environment is what pushed you to constantly find things that are out of your comfort zone?

D

Possibly. I was born in Netherlands, the first language I was exposed to was Dutch. In my head, I even still count in Dutch. But I wouldn’t say Amsterdam as my hometown. Even though I have spent half of my life in Jakarta, I also wouldn’t call Jakarta as my hometown. To think of it, I don’t have a standard idea of what my comfort zone is.

I was accustomed to going out of my comfort zone. There are some people who would avoid staying over in places other than their own home. I never had a problem with that. Since high school, our field trips and community service programs were to visit villages that were very foreign to us. In some experience, we even had to stay with a becak (rickshaw) driver who had no floor constructions. I was first surprised by this, eventually I have grown to be accustomed with discomfort.

A

Other than the uncertainties of your travels, how do you choose your travel destination?

D

When I travel on my own it’s because I am curious of the country. My travel destination would also be based on the roots of anthropology. I have very much been interested in the history of migration. I felt this is something that I can only explore in the academic world.

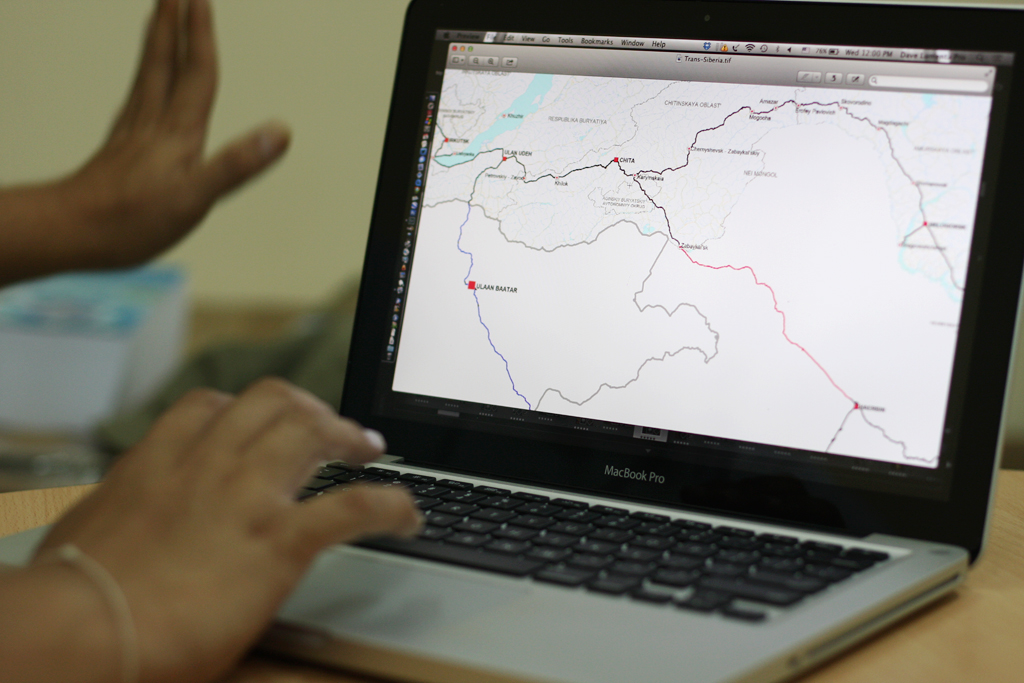

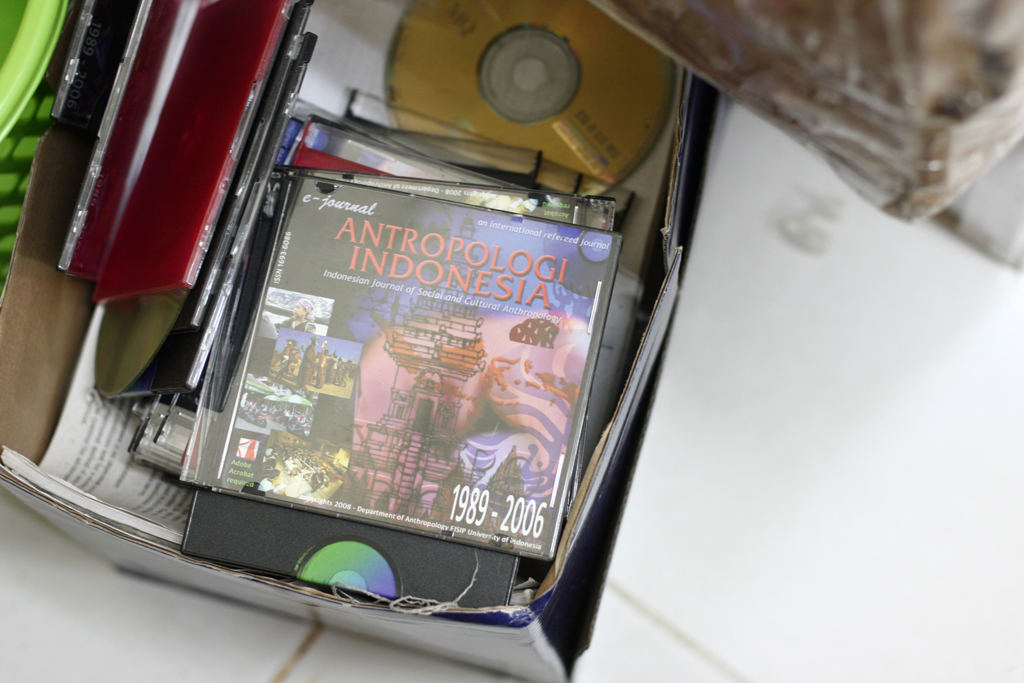

I realize the academic world can provide me with a lot of freedom to explore my interest, I am interested in the migration world, from migration I ended up venturing into something more specific, which is borderlands.

I once attended a seminar and met with a Japanese professor from Kyoto where his main study was borderlands. I made a discussion with him and he mentioned I could study borderlands without a master degree and pursue a research degree with a scholarship. So I put thought into it since I thought I wouldn’t get any younger, I decided to pursue it and primarily focused on Southeast Asian studies. Hence, my choices of travels has always been influenced with my interest in studying migration and borderlands.

A

Why did you end up focusing on borderlands? what is the significance of borderlands to you?

D

First of all, my understanding of borders was when I was in Europe, by crossing a different boundary, you would be exposed to striking differences. From Netherlands to Germany, you straightaway would be exposed to a different language, a different community, and different mannerism. Back then, I thought the whole world operated like that.

When I was in Apo Kayan (Kalimantan), the border differences were a bit arbitrary and were mostly made by the Dutch and British people. The landscapes may look the same, but it was the colonization that made each region different.

What intrigued me was how virtual boundaries are in countries that has been colonized. Africa is like that, the borders has nothing to do with the difference of ethnicity of culture or language. I was mainly concerned because most people I know in Jakarta has the same understanding about borders. Between Malaysia and Indonesia, many would quickly assume we are different. In actuality there are gradual differences between Malaysians and Indonesians. And almost all borders in Asia works in the same manner.

Take Laos and Thailand for instance, when you cross the Mekong River, the dialect of the Thai and Lao people are actually the same. People in Surin province in Thailand has the same dialect as the Khmers in Cambodia, and many from South Thailand speak Malay because they are in the borders of Malaysia.

Because of this, I end up looking for continuity in each borders. I have a mission to this, because I feel borderlands in Southeast Asia are virtual and only the tribes are separated. These borders instead have been made by a number of political actors in the past.

Even in Japan, when we talk about provinces, Okinawa is actually similar to Philippines or Taiwan. I also ended up becoming obsessed with these regions.

If we look at the Southeast Asia map, between Philippines and South of Taiwan, you’ll understand that the language and the ritual to people who reside there are similar to those in East Indonesia. Here I found a different kind of borderline. It’s no longer the borderline between countries. As an island located between the Philippines and Taiwan, with the east side of the island being the Pacific Ocean, and the south being the South China Sea, the two ecology are separated by two oceans. Those in between tend to practice the same rituals and catch the same kind of fish. Because the cosmology of ocean are the same.

Here we can see the similarity of two Southeast Asian countries formed because of the ecology. This is primarily what interests me about traveling; finding things that are familiar in different locations.

A

Do you think these borderlines are important?

D

It is important because we always have to be critical about what we call nationalism. The difference between Malaysia and Indonesia can sometimes be a bit dehumanizing. When someone asks where you’re from? If your answer is Malaysia, people would build their own stereotypes based on the country. Suppose you mention you’re Indonesian, there are many generalization that people can ask you, “Can you eat pork?” can be one of them.

With a country as an identity, people tend to categorize what you can do and what you are like. Sometimes it is a stigma. A nation’s identity can facilitate many things as racism and segregation. That is something hardly seen in in transitional borderlands, identity isn’t as important.

A nation-based identity are most common in centralized cities, in Indonesia it is in Jakarta. If you go to West or East Kalimantan, you wouldn’t be categorized based on the country you are from. They don’t see me as an Indonesian. In Malaysia, I would be considered an “Indon”, but in Sarawak, they would find similarity by proudly announcing that their ancestors are from Indonesia.

Transitional areas tend to be multicultural. They are used to differences.

A

Going through some of previous articles, you seem to be against the idea of globalization. Can you elaborate on that?

D

What bothers me the most is how the image of globalization is used. For instance, when I was at the immigration at Changi, Singapore, my passport was evaluated because it bears many stamps from Thailand, Philippines and many outskirt cities.

That is the reflection of this idea of globalization. If a Caucasian had the same number of stamps on their passport, he would be labeled as a global citizen and would easily be welcomed to Singapore. An Asian will always be questioned if he/she is a terrorist or an immigrant that is running away from their country. This is the image of globalization that we should be critical about.

One of the easiest example if you notice is the airline ads, these days it is always an image of a male Caucasian in first class served by an Asian stewardess, this is subtle racism that is institutionalized. Back then in the 70s, many ads involved families traveling in an economic class and the ones shown are an Indian family traveling.

This made me realize that Asian people are still considered second class global citizen.

The ones that appear to be spearheading globalization these days are businessman or bona fide tourists. What many don’t notice is that the lower class is facing their own form of globalization.

A

But with this idea of globalization, with people speaking the same language, doesn’t that reduce the gap of the borders between each people?

D

Yes and no. What becomes a mockery for globalization with this idea of having a borderless world is the irony of embassies of the world, say in Jakarta, the embassy walls are now taller and are equipped with barbwires. In the 80s, you still were able to park inside the British embassy and you can enter without security check. This becomes a mockery to this borderless world.

This doesn’t only apply to embassy of countries where there are terrorist threats, the embassy of Singapore also have heightened their walls. This clearly shows globalization is only applied to a number of people.

Yes, globalization may be a business term, but it is reproduced and is taken for granted to the point that people now believe we live in a borderless world. We forget about class differentiation, this becomes a apparent that those who can become globalized are upper-middle class. There are also globalized migrant workers, they have the accessibility to move from country to country, but they lack the autonomy as those in the upper class, in the airport, these migrants are more likely to be shouted and scolded by immigration officers.

There is a euphoria of a borderless world, but the truth is stereotypes is becoming prevalent.

A

You mentioned travel makes you analytical, what can be understood from your own country?

D

Traveling used to be a privilege. For the last 6 years, with the availability of budgeted airlines traveling has become much more accessible, especially for the middle class in Indonesia.

Through constant travel it made me realize that Indonesia is still a second-class nation. We still need to have visa to travel to a number of countries. I also feel Indonesia is very self-centered, this is often the trouble of a large nation, we take high pride in ourselves. At least now, since more people can travel, they can see what’s different out there and what things are the same.

Most people have the tendency to see things on surface value, I mean take Singapore for instance, they may have good infrastructure, but the fuel prices are expensive and the tax of owning a car is also extremely high. So it’s good to not only see the good side of travel, but try to dig deeper. There is pro and there is con, so the comparison has to be much more substantial. To improve Indonesia, it is important to have a comparative perspective, if not, we wouldn’t know where we need to catch up on.

A

What’s the most valuable lesson that you acquired so far from your travels?

D

The fact that we learn a lot when we get out of our comfort zone. We tend to have a lot of expectations when we are in our own comfort zone, and we design our travels to fit our expectations, we go to places that are familiar, we meet familiar people that we know we can communicate with and in that sense, we fail to learn something new.

And it becomes something to contemplate on. When we are faced with situations where there are no foreign conclusion or stigma, things become much more interesting.

But the question for myself is because I travel for anthropology reasons, I have a tendency to be very analytical and critical. So whether my travels is transformative for me is something I have yet reflected upon.

I am just afraid that I have become a non-comfort zone junkie — always looking for something different all the time (laughs).