Art and Memories with Saleh Husein

Muhammad Hilmi (H) talks to artist and musician Saleh Husein (S).

H

Seeing as you are both, are you more comfortable as a musician or as an artist?

S

They both offer different types of comforts. When you are on stage, you have finished creating your music – it becomes a matter of performance. In visual art, I do not perform live paintings, there isn’t a performance. I’m comfortable in both fields, but on a personal level, visual art is a more personal endeavor. In White Shoes and the Couples Company I work in a team/band, I have a personal stake in the music but the work is a collective effort. White Shoes is a project, and we all treat it as such. In art it is a product of my personal research and interest.

H

As you grew up, which form of art would you say was closest to you, music or visual art?

S

My mother was a painter, though I have never seen her paint. When she married my father she stopped for one or reason or another, and she gave away her paintings to her friends and others. When we made our way to Surabaya, or my brother’s wedding in Semarang, we of course listened to music during the trip – so music came first. There was one point where I bought cassettes, and that was when I saw the visual in music.

H

As you mentioned earlier, you create art based on research. From what I know of your work, the topics you talk about are very personal/introspective. What are you looking for in terms of creating art when you delve into your research?

S

I believe it started with my solo exhibition. When I create art, it has to be anchored. I can’t just imagine, create my work, and be done with it. Purely expression… what for? All you need to do is go to a club, dance, that is pure expression for me, or ride full speed on a bicycle with no brakes – that is emotion and expression to me.

My work has to be based on something. When I started looking for a subject, I decided I would start with what is closest to me. What was closest to me was a simple question: Why am I here? I am of Arab descent, and my uncle told me that my ancestors traveled here – that was interesting to me because the idea of travel is so visual.

I had the help of curator MG Pringgotono and Ade Darmawan, giving me direction on what topics I should approach. The subject I wanted to talk about initially was violence, because there was so much violence happening in Tanah Abang, where I grew up. They asked me why should I talk about the violence when there are many factors within the violence that I may talk about – I can talk about immigration, family relations, etc – our identity.

I love history, and when you see there is this missing page, you wonder why it is so and must fill the gap – this inspires me to dig to find out what happened. Using my Arabic roots as a starting point, I researched about the politics, when they first entered Indonesia, why my family stayed in Singapore for 2 years before going to Indonesia. I learned the details and context to why I am here.

H

By learning your history, you can express your interest, such as violence, through your work.

S

Yes, but through my solo exhibition, I didn’t include everything. I had to consider whether or not it is necessary to talk about the violence, a particular political situation, the diaspora, etc. I decided to make it more personal, be more autobiographical.

H

A lot of artists create their work in response to social conditions. How do you see your personal, introspective work in comparison to this more ‘current’ expression of art?

S

Although I think that is for the people who observe to judge, personally, when we talk about history, what is happening now is influenced by what happened before – that is for sure. So when we discuss these narrative historical excerpts thoroughly, it can affect the larger narration. I don’t talk about the current context directly.

I’m not saying that talking about something current isn’t interesting; I just choose to address historical events that aren’t popular into a more popular sphere.

H

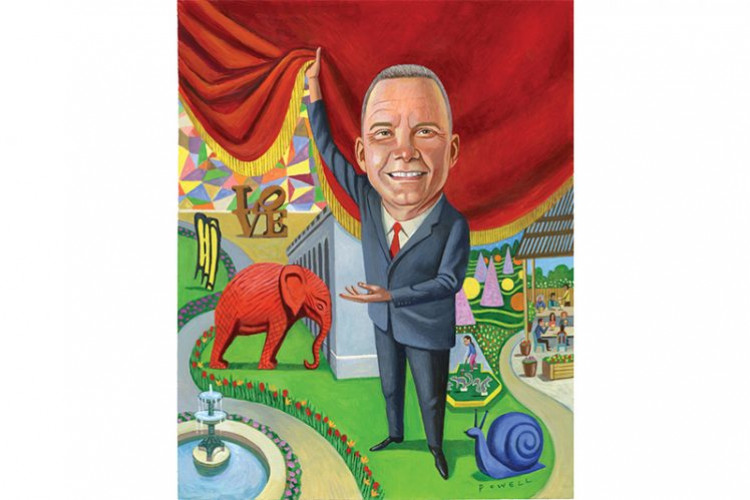

Could you tell us a bit about your work titled Silsilah (Family Tree)?

S

That work talks about family trees in Arab, where patriarchy dominates and inserting the name of a woman into a family tree is Haram. The prophet Muhammad didn’t have children who were boys, so his family tree should have the female names, but it doesn’t – it has the name of his uncles and their sons. The name Muhammad in my work doesn’t refer to the prophet, but my ancestor. I purposely inserted women’s name, and is critiqued because of it. I would retort with facts of history, which creates a ping-pong discussion effect.

My other work, the wedding, is based on the diaspora Arabs. I found that in my generation, there are very little locals who marry people of arab-descent. I was trying to find as many as possible – I found four. It is a rarity, but it wasn’t before. There were many marriages between locals and Arabs, and it helped create the consensus that Arabs were not foreign. So I decided to draw the person of the Arabic groom wearing Indonesian national clothing, and the local bride wearing traditional garb – hence the Arabic men following the women.

H

Why are there less inter-cultural marriages now?

S

Because people want to go back to their roots.

H

When I see your work such as Silsilah, my impression is that if people do not understand the context, your work can seem self-centered. Should we, as the audience, be more informed or is it up to the curator and the artist?

S

When I create art, I try not to illustrate the subject literally – there are metaphors, codes, etc. When you enter a gallery, an exhibition space, you enter an exclusive space where you automatically experience ideas. I do not try to make my work multi-layered and complicated as to confuse the audience, when I create work I research what I would like to talk about and see what medium best expresses my idea.

If there were an explanation then it would come from the curator, or short writings by the artist. I think it isn’t a matter of over-complicated work, because that isn’t my goal, it is a matter of how to see the work.

H

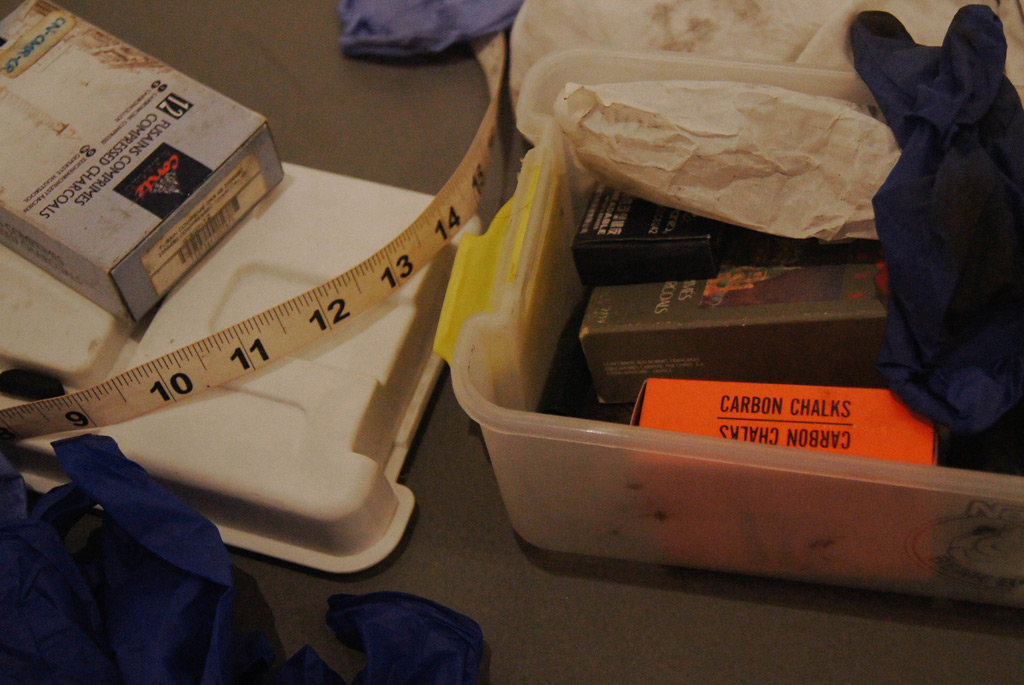

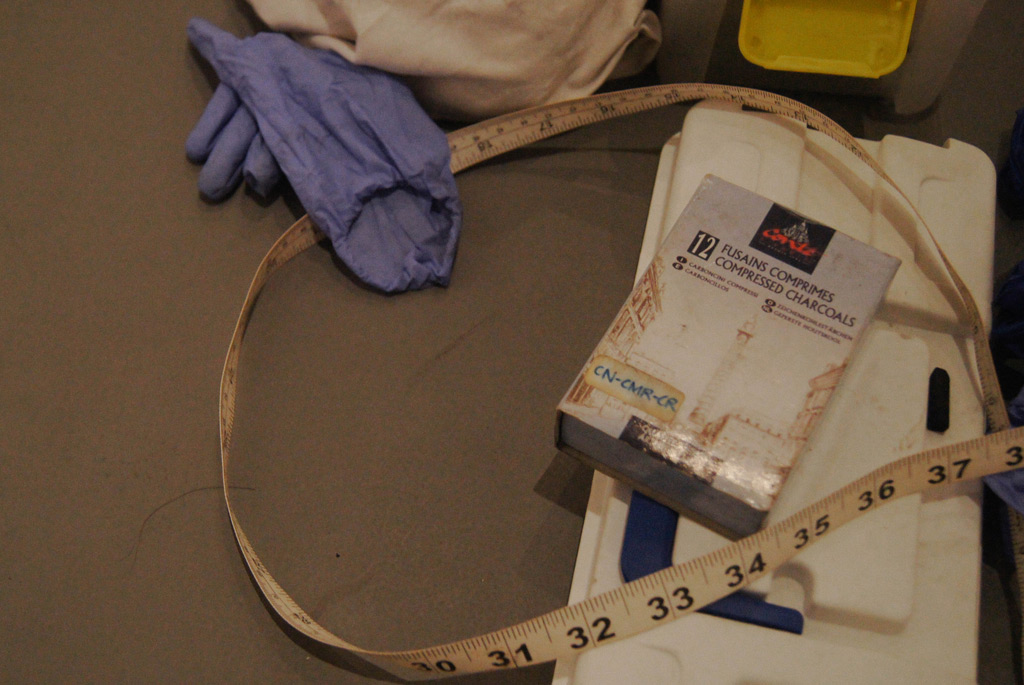

Much of your latest work uses charcoal, is there a reason for that?

S

As I discuss history and memories in my work, the topic became connected with the medium. Charcoal is used to sketch, to record, and remember an idea. So it is a medium that can express the subject of memory, identity, the context of the art.

I do personally enjoy using charcoal because I am fonder of drawing than painting. For commissioned work I always use paint because of the quality and longevity. I draw directly on the wall using charcoal because we are in a gallery, which automatically means that the drawing will exist only for a certain amount of time, which goes back to memory. History can become distorted, erased, or forgotten.

H

Who is your favorite Indonesian artist?

S

They’re all my friends. Ade Darmawan, who discusses objects and the context of socio-politics, Diki Mahardika Indra who creates videos addressing politics, Cut and Rescue – they have their own perspective in their creative process. There are many young artists that are great.

H

How do you see the current Indonesian contemporary art scene?

S

While I was in college I spent more time in the market/industry. When there was a boom in the art scene I wasn’t a part of it, I was observing what sort of work the market demanded. Back then what artists followed the market, now they are based on research. Artists now anchor their work based on a collection of information.

I forgot to mention this earlier. I read a book of critiques on visual art, there was a writing by Sudjojono that said in the past, the message of art was clear – it was for the revolution. What do people create art today? This made me question the reason why I was creating art. Art must be able to be studied, it needs logic, it needs a clear context. This is so your art isn’t just an object hanging on a wall, it has a life, a documentation that can be studied. Interestingly enough, there have been 3 or 4 of my work being used for a thesis comparing visual art, religion, history, how an Indonesian work compared to a Chinese artist.

H

You are one of the artists who appeared during the golden age of Institut Kesenian Jakarta (IKJ) and Ruang Rupa. What would you say is the reason the artists from that era are still relevant today?

S

The artists are relevant because they are still constantly looking to create something new, being forced to reimagine and to think. It isn’t a matter of visual art, it is a matter of their way of thinking and the ideas they bring to the table.

12-13 years ago, there were no alternative art spaces, every gallery was commercial. Ruang Rupa created an art space where young artists can create art that were wild yet well-thought out – that is very cool. I became close with Ruang Rupa because I made Jakarta 32, I was invited to create an exhibition with 4 campuses. I suggested that we don’t limit ourselves and invite all campuses to create an exhibition.

As long as you are restless – you aren’t comfortable – you will keep searching for something new.

H

So what makes you restless? How do you keep yourself motivated to keep searching?

S

I believe that I am motivated because I am surrounded by a community who are motivated (Ruang Rupa). I think I am at the right place and am surrounded by the right references. In music, I listened to hardcore and metal, which rooted me in a certain way of working and creating. If I was hanging out in the wrong surroundings, I wouldn’t be able to approach my music this way, or create it the way I do today.

When you live in the right era, you have a choice where you would like to position yourself.

H

How is it to be in a band with members that are also in visual art (White Shoes and the Couples Company)?

S

There is a visual understanding between the members. When I am with the Adams, they ask me to create the visuals. In White Shoes, three of the members are visual artists, the other three are musicians, which forces you to collaborate in creating the imagery.

H

What is it like to live as an artist in Indonesia? You said before that with your parents’ reservations, you lived in a world that is perhaps strange for an artist.

S

My parents are no longer around, so I am supported by my siblings.

Oh, I have a good story. When I was in grade school, I asked my mom for money so I can go to a PERSAMI [Perkemahan Sabtu-Minggu, a weekend boy scout activity]. My mother didn’t have money so she wanted to go to the bank first, but I insisted that I wanted to leave right away. My older brother then said to me “if you want to be a boy scout for the rest of your life, I will pay for this trip, I’ll even double it, but you must be a boy scout for the rest of your life.” I was in sixth grade, my friends were waiting downstairs, and I was made to think about a life lesson in responsibilities. I went downstairs and told my friends I wasn’t going with them. I went back upstairs and sat watching Doraemon, but I actually wasn’t watching – I was thinking about what my brother said.

When I went to college in Institut Kesenian Jakarta, I had an exhibition and my whole family came to see it. The same older brother asked me if I was sure this is what I wanted to study, and that I would do this for the rest of my life – I replied “yes, this is what I wanted to do.”

I have a moral responsibility to my family, even if I didn’t finish my studies in IKJ. As long as I can think and have a clear idea, I should express them whether in visual art or in music.

See, I inadvertently told you a story from the past to explain the present (laughs).

—