Film Craftmanship with Mouly Surya

Athina Ibrahim (A) sits down with film director Mouly Surya (M)

A

Can you tell us how you got into filmmaking?

M

Since I was little I enjoyed reading. So my interest wasn’t necessary in film. Films back during the new regime were difficult to acquire. I would normally rent out laser disc to watch instead. I guess I can say my interest was in storytelling. I enjoyed both reading and watching. Mostly it would be Japanese Manga (Anime) and not novels.

After I graduated high school, I wanted to study at IKJ (Jakarta Art Institute) but my dad didn’t allow me. So I ended up taking English Literature because a part of me always wanted to be writer. Then I studied in Australia, where I took media and literature.

In Australia, there were many Indonesian students and communities and some would spare their time to make their own films. I had a friend who suggested we make our own film. So I did and enjoyed it, I then continued my masters in filmmaking. When I came back to Indonesia, I did some internships and helped out to be an assistant director.

A

Was your interest in literature what propelled you to study Media and Literature?

M

It did, but Media and Literature in Australia pushed us to analyze various work of literature as Salman Rushie and other materials that at the time I found difficult to digest. I could speak English but the literature we had to examine was complex in its theory and expression.

There was a point where it felt troubling for me to read literature. I still enjoyed reading, but I didn’t feel I wanted to write to make a novel. I like expressing myself in words through my blog but making a novel wasn’t my intention.

A

How did your interest in literature then help you in your filmmaking?

M

There was a number of the literature course that was made to dissect and understand aspects of literature. But in those years, in the early 2000s, the Internet became the third strongest medium. So the course was geared towards how the art world would change within the changes of the digital world.

The most important aspect of what I learned there was how to be a smart audience. We were taught to appreciate art as a whole by becoming a humanist. We had to train ourselves to look at culture through a critical point of view.

I realized I developed the ability to interpret artwork in my bachelor years and that became very useful when I pursued film as my masters. Students in Australia were very outspoken and had the knowledge to interpret films and initiate film discussions. That’s what I don’t normally get here in Indonesia and most Asian countries. There is a tendency for information to be dictated and students to be spoon-fed.

A

You first started making films as a student in Australia, but only became serious upon your return to Jakarta. How would you define the conditions when you first started making films?

M

It’s difficult to compare between making a student film and an actual film where the involvement of a greater team were needed. There were more than 10 to 20 people.

I was in Australia for six years. I was far from my parents and found that I grew up the most during my time away. So upon my return I found myself being detached from the environment I was once familiar with. I had to adjust and search for myself again.

There is a tendency for kids who studied abroad to – this may sound a little arrogant – experience culture shock in their own country. Even though during their stay they mostly hung out with the Indonesian kids. But if you think about it, there is less number of filmmakers here in Indonesia who actually graduated from abroad although a great number of Indonesians actually do study abroad. This is simply because you see a big cultural gap that any Indonesian has to adjust to when they return. Indonesians have very close-knit communities. Once you come back, you don’t necessarily fit well within the communities. You’re back to being an outsider.

Back then I wasn’t solely evaluating the film industry. The process of re-adapting was my main concern.

A

Your husband, Rama Adi, is the producer for both of your films. How was it like working with your husband? Does it happen naturally?

M

It’s complicated! (laughs) Probably from an outsider’s point of view it is too complicated and not ideal. For me it feels most ideal and I consider it one of my strengths. I believe because of our relationship as husband and wife, we don’t have any restriction towards each other at all. When we critic each other, it can be brutal. He is my worst critic and vice versa. If there was a professional relationship between two people I would assume it wouldn’t be that comfortable. There would bound to be some courtesy that we people would hold towards each other.

For Rama and I, any courtesy is out of the window. It is like raising a child. The most important thing at the end of the day is our child. The same applies to our film as well. In the end, there isn’t any pride in me where I go, “This is my job scope. I have to be the one doing this.” We have the ability to discuss matters as openly as possible. In the end the goal is the film itself.

A

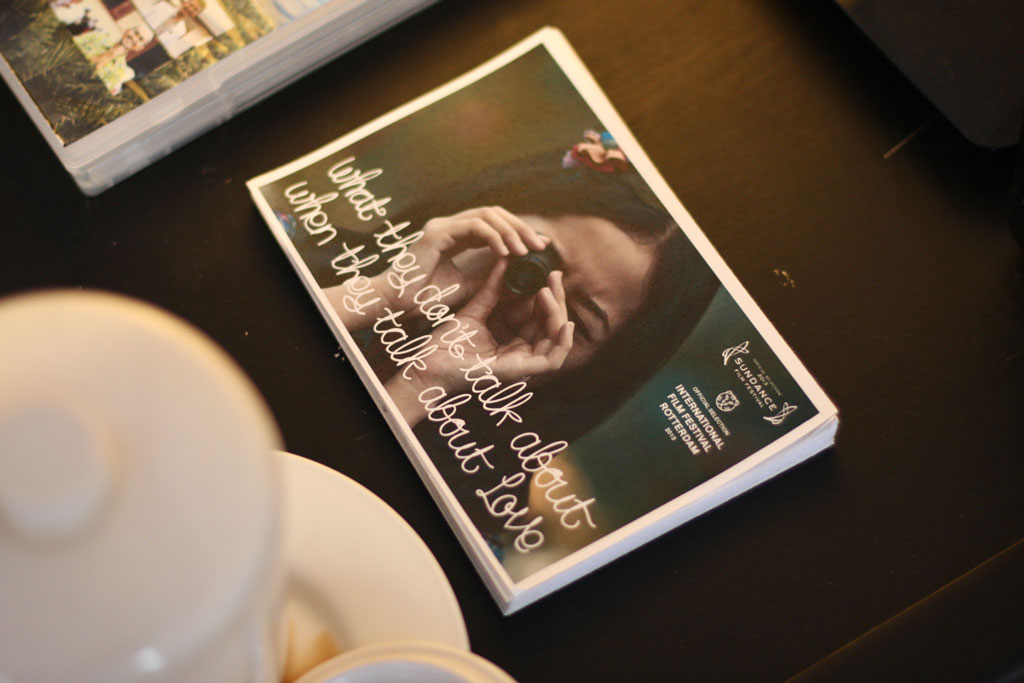

You latest film, Don’t Talk Love… was selected for Sundance. Is there extra pressure for you to deliver your next film?

M

I don’t feel that sort of pressure. When I created Don’t Talk Love… I did feel anxious but it wasn’t to the point where I stayed up all-night and thought about the responses towards the film. I don’t associate the pressure to be only with Sundance. I think it’s only human nature. Suppose we draw something, it’s only natural to want our second drawing to be better that the first. Regardless whether the first drawing won awards or not, we would still want to create something better than before.

Sundance was a great stepping stone. It did make certain things easier for us. But as the case with Fiksi, it won a Citra award. I don’t think I made a big deal out of it.

I don’t want to be affected by all that media hype. I see these awards as recognition, but I make sure I don’t loose objectivity in seeing the two films I made. These awards and festivals are only brands and what it did for me was gain an a larger audience who first wouldn’t know of the films without the Sundance or Citra label on it.

A

Do you still feel a need to prove yourself to others or even to yourself in the film industry?

M

I don’t feel that I have to prove myself to anyone. I mean, I know that it is something that’s pretty common. I realized that there is that tendency, while I’m teaching for people to prove themselves to other people. It is human nature. I’m not aware of that need personally. I’m the type that likes to be able to do whatever I want to. I do not want to be a famous director because the name Mouly Surya is not important to me.

I don’t like being the centre of attention. Maybe I’m still pretty new to this, so there is spite to it. There is a sort of celebrity status being tagged to a director and you end up unable to be a true artist. It becomes more complicated because I’m a woman. There is beautification of image involved and when you’re in a magazine, as a career woman, they love to categorize you as a female director. In the end, there is this celebrity status that is uneasy because, in my opinion, it reduced someone’s sincerity to create something.

The adherence of “Mouly Surya’s film” is unnecessary. However, sometimes, it is needed in order to promote the film, whether you like it or not, especially when a director’s name has morphed into a brand. Such as Steven Spielberg, even though he seldom directs now, his name is still often used on a film. That’s the kind of name branding I’m referring to. It is something that we can’t avoid. I feel that it is a kind of liability and advantage. It maybe easier to sell a film with a famous name however, it might create a bigger hurdle for the director personally.

A

Have you ever felt a conflict to work on something commercial with something more idealistic?

M

Not really. To me, I don’t think I have to take on a commercial job just because I need to put food on the table. I mean I have to put food on the table either way, even with what I’m doing now. In my opinion, there shouldn’t be a differing status between commercial work and your ideals.

Why should there be a conflict? Why do I need to choose? For me, I just want to make a film that has character and which I can be responsible for. It doesn’t make sense to me to take on a commercial job just so I can just survive.

I don’t have the dream to own a Mercedes and own a huge mansion. So far, my life has been sufficient for me. If I wanted a lavish lifestyle, I’d probably be a businesswoman in the first place. So far, I’m content with what I have.

A

What is your current obsession? Other than the film you are currently making, is there something you are really interested in?

M

I think I have a range of interests. Currently, because of the fasting month, my teaching period is on a break. There aren’t many activities that I’m also doing at the moment.

But If I was interested in something, I would be very much into it. Surprisingly, I am not someone who always watches a film. I don’t watch two films a day and even for a week I wouldn’t watch a thing.

In general, I am always interested in arts and culture, so if I’m not watching a film, I can enjoy other work of arts. For example, last week I just watched a live broadcast at Blitz Megaplex of a ballet performance in the Mariinsky Theatre, Russia. It was in 3D. I have been hooked on that since, so I ended up watching Swan Lake performances on DVD, and understood now that the Swan lake performed in Russia is different to that in America.

Things like these answer to my sense of curiousity, I would watch documentaries on TV or on youtube to understand the little details that people might find unimportant. For days, I could indulge myself in documentaries of plane crashes. I mean it doesn’t make me paranoid, but only more cautious when I am on a plane.

A

Since you teach film in a university. Can you tell us your observation of the film industry and the potential we have now?

M

First and foremost, I see myself as an artist and a practionationer. I’m not an activist. I am not certain I am the right person with the right knowledge to talk about our film industry.

I feel by teaching I am already contributing what I can do to the film industry. Maybe my film cannot be enjoyed by five to six million people yet because the nature of the film itself. So how I can contribute to the industry without being against my idealism is by teaching. And I really enjoy it. Being in a film school once is what brought me here, so I felt I wanted to go back and give what I know. I realized this is important to the industry, because it gives what the industry needs now. And that is human resource.

A

Do you believe theory is as important in filmmaking?

M

Of course, a large amount of my teaching favors theory with almost no pratical work included.

In my opinion, eventhough it won’t apply to everyone, I am not talking about feeding the students with bulky theoretical thoughts but there are convensions in filmmaking people should understand before they start filmmaking. A degree of knowledge has to be learnt to understand a film within the first five minutes of its inception. Think of it as a language. I see film as a language to communicate. Filmmakers need to understand this visual language.

I don’t believe in an instinctive filmmaker, moreover I don’t believe in talent. There is basic knowledge about filmmaking that people need to acquire if they are truly interested in their craft.

A

What is the next step for you? What will you explore next?

M

I’m currently teaching myself Japanese. It’s not related to filmmaking at all.

I don’t have plans five to ten years ahead of me. I just see how it goes. I can’t really explain because I don’t have a special target. I’m not overly ambitious and pretty content with what I do. But when I do something, I’ll give my 200% especially when I was directing Don’t Talk Love. There is a point where, taking the analogy of a game, my energy level was reduced to a critical condition. Afterwards, I’ll need to rejuvenate again to recover myself back to a healthier state. That happened when I was directing Fiksi. I was only focused on that for years. Actually, I’m someone who is very passionate. My husband as my producer is a pretty calm personality, he would often advise me to wind down when I need to. It’s like love itself. When you have too much fiery passion, it burns up easily. That’s why I try to look for a calmer process and just absorb everything at first and see how it goes.

A

So there isn’t anything concrete in the plans at the moment?

M

There is nothing that is concrete. One of the biggest risk of being a filmmaker is often you will not find anything concrete when carrying out a project. For example, next week shoot might not happen as planned. It’s unpredictable and I experienced it first hand while shooting. There are so many things that I wanted to do and it never materializes. I have to change my approach; I need to find a new form as soon as possible. I need that fluidity like, “Alright, this glass is not enough to contain the liquid, we’ll need to change it.” There is no right and wrong when it comes to that, only what works and what doesn’t.

That’s how I approach my work, by trying to be as flexible as possible, even when I’m not that flexible myself.