When the World Seems to Forget the Repercussions of Colonization, This Art Exhibition Presents a Much-Needed Reminder

“Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asian and Latin American Art,” when art speaks louder about the Idea of colonization than your typical government.

Words by Whiteboard Journal

Text: M. Hilmi

Photo: National Gallery of Singapore

In recent years, there has been a rise in discussions related to the concept of the Global South. “The Global South” here refers more to an idea than a specific geographic area, traditionally encompassing regions of Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania. It’s often used in contrast to the “Global North,” which includes North America, Europe, and other wealthier parts of the world. The term goes beyond mere geography, encompassing economic, political, and cultural dimensions.

Many countries in the Global South have experienced significant economic growth. With this growth, there’s a growing recognition of the importance of diversity in the arts and culture. International festivals, exhibitions, and events increasingly feature artists and cultural works from the Global South, recognizing their unique perspectives and contributions. There’s also a growing global interest in indigenous and local cultures, which are often rooted in the traditions of the Global South. This interest has led to increased appreciation and promotion of these cultures in the global arts scene.

But how do we, as Southeast Asian people, react to this phenomenon? How should we respond when more and more spotlight is placed upon our culture? How can we avoid the tendency towards objectification and exoticism that often leads to exploitation and—god forbid—neo-colonialism?

Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America addresses these concerns head-on. This art exhibition presents itself as a compass for us, the Global South public, on how we should understand ourselves first before letting others perceive us. More than anything, this exhibition redefines the term “tropical”—liberating it from derogatory and unrealistic stereotypes of a native paradise. And what better way to do that than to take a look into our own history?

(Photo: National Gallery of Singapore)

Presented in a retrospective narrative, Tropical parallels how artists in Southeast Asia and Latin America have liberated themselves from colonialism’s ideas of our culture. The exhibition invites the public into a captivating historical lesson that revolutionizes the idea of the term “tropical” itself. This exhibition emancipates us from the exotic label of tropical, which usually aligns with unrealistic and often derogatory ideas of native paradise, and then invites us to seek beyond those labels to find our own identity, fostering solidarity.

(Photo: M. Hilmi)

The exhibition’s impact is immediately felt in its entry area, where visitors are greeted with the powerful words of liberation, “THE MYTH OF THE LAZY NATIVE,” a title taken from Syed Hussein Alatas’ book that debunks the colonialists’ construction of the locals in Malay, Javanese, and Filipino cultures. This idea is then elaborated through a series of presentations that put Southeast Asian arts alongside Latin American arts, finding kinship in both situations. Alongside the arts, they display a set of manifestos that made the idea of liberation even more apparent in both regions, even in the early years of the 1920s:

“Without us, Europe would not even have its poor declaration of the rights of man. The golden age proclaimed by America. We walk,” said Oswald de Andrade from São Paulo, 1928.

“Realism does not belong only to the West. Realism belongs to all of us, to every human being,”

This idea continues to develop further and sharper in the upcoming years. And not only that, this kind of liberation also resonates across the thousand miles that lie between Southeast Asia and Latin America. Consider this passage from S. Sudjojono:

“As Indonesians, we admit that the art we make here nowadays has a Western style. Nevertheless, to say that it is not an Indonesian style is not accurate. Realism does not belong only to the West. Realism belongs to all of us, to every human being,” from Jakarta, 1947.

And see the same kind of idea shared by Helio Oiticica—a Brazilian visual artist, sculptor, painter, performance artist, and theorist, best known for his participation in the Neo-Concrete Movement:

“For this reason, I believe that Tropicalia, which encompasses this entire series of propositions, came to contribute strongly to the objectification of a total ‘Brazilian’ image, to the downfall of the universalist myth of Brazilian culture, entirely based on Europe and North America, and on Aryanism, which is inadmissible here,” from São Paulo, 1968.

Installation view, Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore, 2023. (Photo: National Gallery of Singapore)

What makes the idea of liberation present louder in Tropical is their approach to art presentation. For this, they adapted the idea of Italian-born Brazilian modernist architect, Lina Bo Bardi, in art architecture: “It was my intention to destroy the aura that always surrounds a museum, to present artworks within everyone’s reach. To revitalize painting, liberating it from the role of a mummy.” The result is an uncommon experience of art that encourages attendees to interact more with artwork/paintings in a way that is unthinkable in common museum spaces.

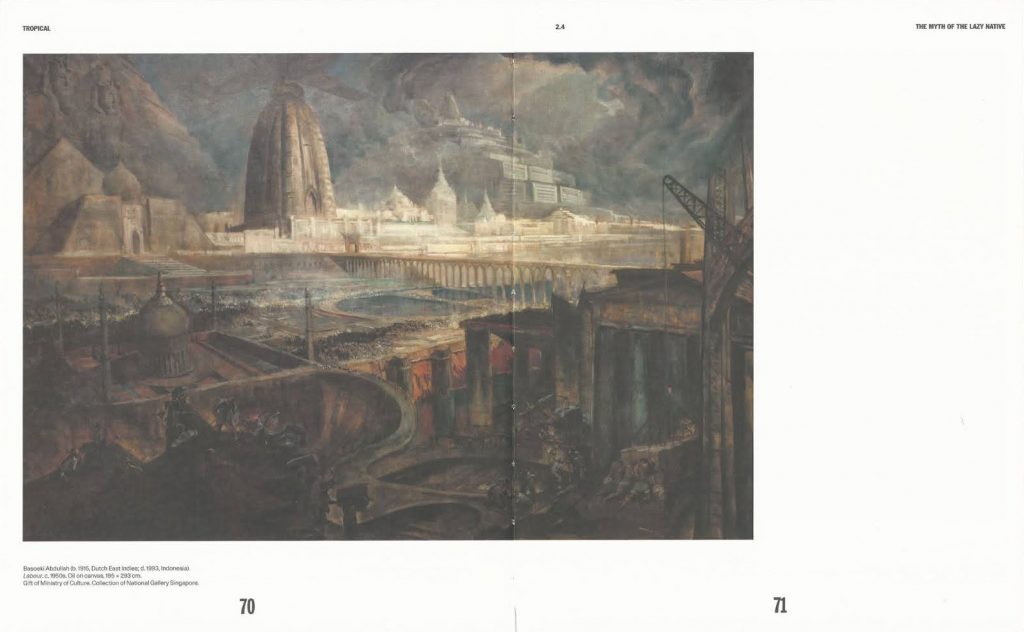

As an opener, this area focuses on how Southeast Asian and Latin American artists portray the society around them to counter the westernized image of the society. One of the examples is Basoeki Abdullah’s “Labour”, where Basoeki contrasts the image of the Seven Wonders of the World (pyramids, Borobudur, to Taj Mahal) with the workforce that built those buildings. This perspective of the third world man trying to understand the state of his country’s post-colonial era demonstrates how progressive the idea of liberation was back then.

(Taken from Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America catalogue)

To liberate yourself sometimes means that you have to reclaim the unrealistic portrayal of yourself from the outsider. This is the idea that came to mind in The Library of The Tropics area, where they display portrayals of tropical images by the West, complemented by displays of books that show how the West often devalue the complexity of our homeland into a simplistic image of exoticism—much like what can be found in Eat Pray Love. One of the most striking parts of this area is the display of “Museum Nusantara”, a collection of souvenirs collected from the VOC’s returning officers that is then shared with new officers who will be posted in Indonesia. It’s a clear example of how the exoticism of tropical nations is taught and preserved by certain modus operandi.

(Photo: National Gallery of Singapore)

Continuing the idea of the book titled area, the second area titled “This Earth of Mankind” – taken from one of Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s most famous books based on Pram’s personal experience of how he and many people of that era reclaimed their own identity during the early era of post-colonialism. It’s a perfect title that welcomes us to the section where we are presented with artworks from Southeast Asian and Latin American artists on how they identify themselves and then share their idea of identity with the world.

Installation view, Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore, 2023. (Photo: National Gallery of Singapore)

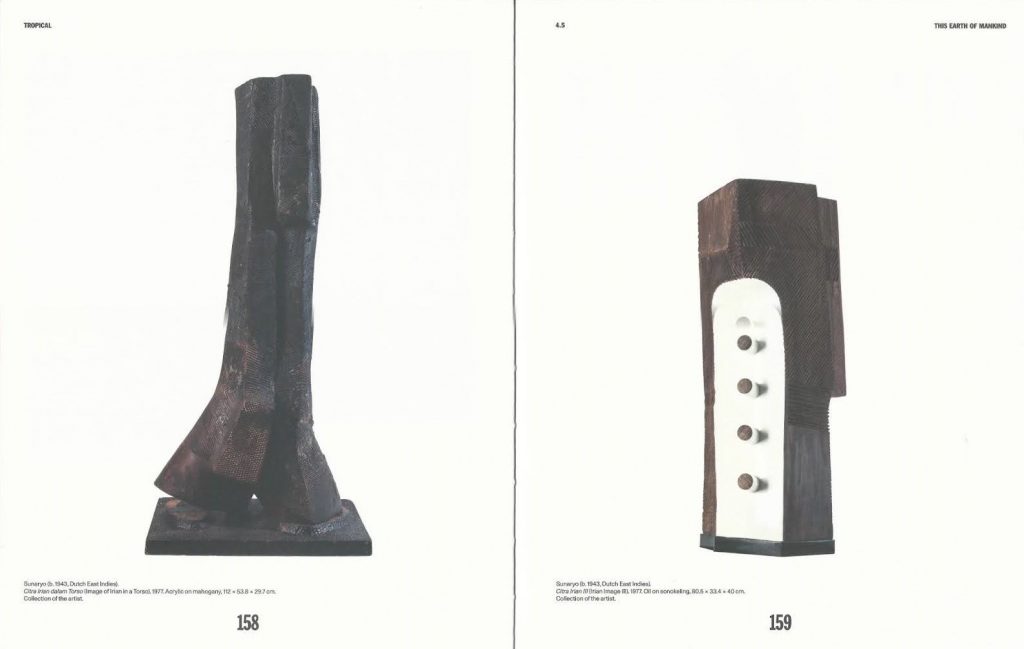

In this area, we focus on the personal identity and portrayal of the artist. Personal portrayal, combined with local attributes such as batik and other cultural assets, shows how artists in Southeast Asia and Latin America also explore this idea through art. One of our highlights is how this exhibition also explores how tricky the process of finding our identity is. The incident involving Semsar Siahaan’s decision to burn Sunaryo’s sculpture is a pivotal moment in Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asian and Latin American Art. This act was not merely a moment of artistic critique but a profound statement on the lingering effects of colonialism on cultural expression and identity.

Left: Patrick Ng. Self-Portrait. 1958. Oil on paper, 49.3 x 75.3 cm. Collection of National Gallery Singapore. This acquisition was made possible with donations to the Art Adoption & Acquisition Programme. © Family of Patrick Ng.

Right: Frida Kahlo. Self-Portrait with Monkey. 1945. Oil on masonite, 60 x 42.5 cm. Collection of Robert Brady Museum. © 2023 Bank of Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. May 5. No. 2, col. Center, alc. Cuauhtémoc, cp 06000, Mexico City. (Photo: National Gallery of Singapore)

Sunaryo’s sculpture, which incorporated elements from West Papuan and Asmat cultures, was perceived by Semsar as embodying a Western modernist logic of “borrowing” from and reworking the “exotic.” This perspective is rooted in a long history of Western modernist artists drawing inspiration from non-Western cultures, often lacking a deep understanding or respect for the cultural significance of these elements. In the case of Sunaryo’s work, Semsar saw an appropriation of West Papuan culture, a culture still grappling with the effects of ongoing colonialism and political strife.

(Taken from Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America catalogue)

West Papua’s history is marked by complex political and cultural struggles. Despite Indonesia’s formal control over the region, there have been ongoing conflicts and calls for independence. The use of West Papuan cultural symbols in art, therefore, becomes a sensitive issue, loaded with implications of political power and cultural sovereignty.

Semsar’s act of burning Sunaryo’s sculpture can be interpreted as a radical statement against this backdrop. It was an act of re-appropriation and re-commodification, a forceful response to what he viewed as a continuation of colonial practices in art. By setting the sculpture ablaze, Semsar was not just critiquing an individual artist but challenging a broader system where the cultures of colonized or politically marginalized groups are often co-opted without consent or thorough understanding.

(Photo: National Gallery of Singapore)

This incident highlights the complexities and challenges of self-identification and cultural expression in post-colonial societies. Artists in these contexts must navigate a landscape where their work is not only a reflection of personal or aesthetic choices but also a statement on broader cultural and political realities. The act of creating art becomes intertwined with historical narratives, power dynamics, and the ongoing struggle for cultural autonomy and respect.

In Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, the narrative of Semsar’s fiery critique serves as a stark reminder of the delicate balance artists must strike in representing cultures, especially those that have been historically marginalized or colonized. It underscores the need for artists to engage with cultural elements responsibly and respectfully, acknowledging the historical and contemporary contexts that shape these cultures.

This incident is a microcosm of the larger theme of the exhibition: the ongoing struggle to define and assert cultural identity in a world still shadowed by the legacy of colonialism. It reflects the ongoing dialogue and tension between preserving cultural integrity, challenging historical narratives, and embracing artistic expression in a globalized world.

(Photo: National Gallery of Singapore)

The exhibition culminates in an area titled “The Subversive,” delving into the abstract aspects of identity and the darker sides of the museum space. It’s a space that invites contemplation and confrontation, urging visitors to confront uncomfortable truths and histories.

Lygia Clark. Máscaras sensoriais (Sensorial Masks). 1967. Proposition; cotton

canvas masks with herb sachets, shells, sponge and steel wool. Courtesy of

Associação Cultural “O Mundo de Lygia Clark”, Rio de Janeiro. (Photo: National Gallery of Singapore)

Aren’t you aware that before you talk about BEAUTY, you (and I) have a moral obligation to liberate those who suffer from ignorance and deception? Don’t we have to liberate those who suffer because they have lost their rights? It is clear, as clear as black and white, that individual freedom is a collective effort to liberate those individuals, including myself, who are struggling to free themselves from desolation.

Hélio Oiticica. Tropicália. 1966–1967, remade 2023. Wooden structures, fabric, plastic, carpet, wire mesh, tulle, patchouli, sandalwood, television, sand, gravel, plants, birds, television and poems by Roberta Camila Salgado, dimensions variable. Collection of Projecto Hélio Oiticica. Image courtesy of Projeto Hélio Oiticica and National Gallery. (Photo: National Gallery of Singapore)

The exhibition does not merely end with a reflection on the past. It opens a dialogue about our present and future. As visitors leave the exhibition, they’re invited to continue their journey of self-discovery and sympathy at the National Gallery of Singapore’s long-term exhibitions: “Siapa Nama Kamu?” (What’s Your Name?) and “Between Declarations and Dreams: Art of Southeast Asia since the 19th Century.” These exhibitions further explore the identity and dreams of Southeast Asia, offering a deeper insight of the region’s diverse cultural landscape.

Tropical is more than an exhibition; it’s a clarion call. It compels us to reevaluate our roles as global citizens, to confront the shadows of our colonial past, and to embrace a future grounded in understanding, solidarity, and collective liberation. It’s a testament to the transformative power of art in shaping socio-political consciousness and fostering global unity.

In an era increasingly defined by the notion of a “global citizen,” it’s imperative to comprehend the roots of this collective identity. Our journey towards global citizenship is significantly influenced by the liberation from our dark past of colonization. This historical journey has not only shaped our individual and collective identities but also the very fabric of our global interactions.

Global citizenship extends beyond traditional borders, fostering empathy, understanding, and solidarity across diverse cultures, as emphasized by the Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America exhibition. Embracing this identity necessitates a thorough understanding of our cultural and historical backgrounds, especially acknowledging colonialism’s lasting impact. It’s about staying connected to our roots while appreciating the rich tapestry of global diversity.

The lessons and narratives from Tropical remind us of the ongoing battle against oppression and the importance of continuous activism.

This journey towards global citizenship is not only about recognizing our unique cultural narratives, but also involves a strong commitment to upholding human rights and fighting against oppression. It calls for solidarity with those struggling for freedom and equality worldwide. The lessons and narratives from Tropical remind us of the ongoing battle against oppression and the importance of continuous activism.

Thus, becoming a global citizen is more than transcending geographical limits; it’s about embracing our history, understanding our identity, and committing to a world where freedom, dignity, and human rights are not mere ideals but lived realities for all.

Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America serves as an enlightenment for us regarding our shared past, and also as a guidance towards a future where understanding, respect, and solidarity are the cornerstones of our global community. Tropical is not just a showcase of art; it’s a profound educational journey and a strong political statement, encouraging a re-examination of colonial history and its ongoing effects. The exhibition is a vibrant tapestry, weaving together disparate threads of shared experiences and struggles across continents.

—

Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America

18 November 2023 – 24 March 2024

City Hall Wing, Level 3, Singtel Special Exhibition Gallery and various locations around National Gallery Singapore

Admission fees apply.