How the Lifelong Works of an Artist Remind Us that Humanity is What Makes Art Truly Captivating

A review of “Liu Kuo Sung: Experimentation as Method”, currently on display at the National Gallery of Singapore.

Words by Whiteboard Journal

Text: M. Hilmi

Photos: National Gallery of Singapore

The year is 2024. We find ourselves in a possibly dystopian (or utopian?) epoch where Artificial Intelligence edges ever closer to our daily existence. Just recently, Elon Musk achieved a milestone by successfully implanting Neuralink technology in human subjects. In Indonesia, political figures are using AI for campaign posters, a trend now echoed by the ad-interim governor of Jakarta who utilizes an AI-generated image for public service announcements. Amidst these developments, the art world is abuzz with debates, as Stephen Marche articulates in his article for The Atlantic, “We’re Witnessing the Birth of a New Artistic Medium”:

“Creative artificial intelligence is the latest and, in some ways, most surprising and exhilarating art form in the world. It also isn’t fully formed yet. That tension is causing some confusion.”

The ethical implications of AI in art and its broader impact on society are subjects that demand ongoing discourse. However, by delving deeper into how humans engage with and create art, we may gain a more informed perspective on AI-generated art.

The “Liu Kuo Sung: Experimentation as Method” exhibition features artworks by artist Liu Kuo-Sung, revered as the “Father of Modern Chinese Ink Painting” in Taiwan and a trailblazer in modern Chinese painting, beckons us to explore human perception and processing of art. Liu’s significance in the visual art world, particularly in the Chinese ink tradition, is underscored by his deep immersion and subsequent redefinition of the genre itself.

Liu Kuo-sung. Dance of the Black Ink. 1963. Ink on paper, 47 x 85 cm. Gift of The Liu Kuo-sung Foundation. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

In the 1960s, at the genesis of his artistic career, Liu Kuo-Sung revolutionized Chinese ink painting with his innovative techniques. He crafted a unique type of paper, distinguished by its coarse, fibrous texture. This innovative medium, when interfaced with ink, allows for the strategic removal of fibers, unveiling striking white lines and textures that lend a dynamic visual allure to his creations. The “Dance of Ink” segment of the exhibition provides a deep dive into the textural nuances of this paper and its integral role in Liu’s artistic expression.

Installation view, Liu Kuo-sung: Experimentation as Method. National Gallery Singapore 2023. Image credit: Joseph Nair, Memphis West Pictures

After his graduation in 1956, Liu was instrumental in establishing the Fifth Moon Group, envisioning a modernist haven unshackled from the traditionalist and nationalist constraints of that era in Taiwan. This coalition of avant-garde painters in Taipei stood resolute against misinterpretations of their aesthetic rebellion as political dissent, steadfastly defending their artistic vision.

Throughout his artistic voyage, Liu seamlessly blended Western art principles with the conventional Chinese brushwork. This synthesis re-envisioned the concept of abstraction within Chinese ink painting, giving birth to a unique visual lexicon that harmonized with the quintessence of nature and echoed the aesthetic principles of classical Chinese landscape art, albeit infused with a modern sensibility.

As Liu navigated the confluence of Eastern and Western art traditions, he acknowledged a universal quest for artistic liberation. Drawing inspiration from the annals of Chinese art history, he discovered correlations with the radicalism he revered in Western avant-garde circles.

Installation view, Liu Kuo-sung: Experimentation as Method. National Gallery Singapore 2023. Image credit: Joseph Nair, Memphis West Pictures

Installation view, Liu Kuo-sung: Experimentation as Method. National Gallery Singapore 2023. Image credit: Joseph Nair, Memphis West Pictures

Installation view, Liu Kuo-sung: Experimentation as Method. National Gallery Singapore 2023. Image credit: Joseph Nair, Memphis West Pictures

Liu unveiled that pivotal figures in Abstract Expressionism, such as Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Antoni Tapies, and Cy Twombly, were profoundly shaped by the calligraphic elements intrinsic to ink art. Mark Tobey’s engagement with Chinese calligraphy in the 1930s is a further testament to this symbiotic interaction between Eastern and Western art, spanning the realms of abstraction, figuration, and minimalism.

He discerned that Chinese painting, with its rich heritage, had anticipated Expressionism by centuries. Yet, it was in the 20th century that Abstract Expressionists became torchbearers, thrusting the legacy of ink painting into a new era. In response, Liu recalibrated his focus, gleaning from historical insights to contemporize his artistic methodology.

This paradigm offers profound comprehension of the evolutionary trajectory of art. Since the 18th century, Chinese ink art has etched its influence onto Europe, shaping diverse artists and movements, including Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism. This influence, marked by its emphasis on simplicity, spontaneity, and equilibrium, has profoundly sculpted global art forms and catalyzed cross-cultural artistic exchanges.

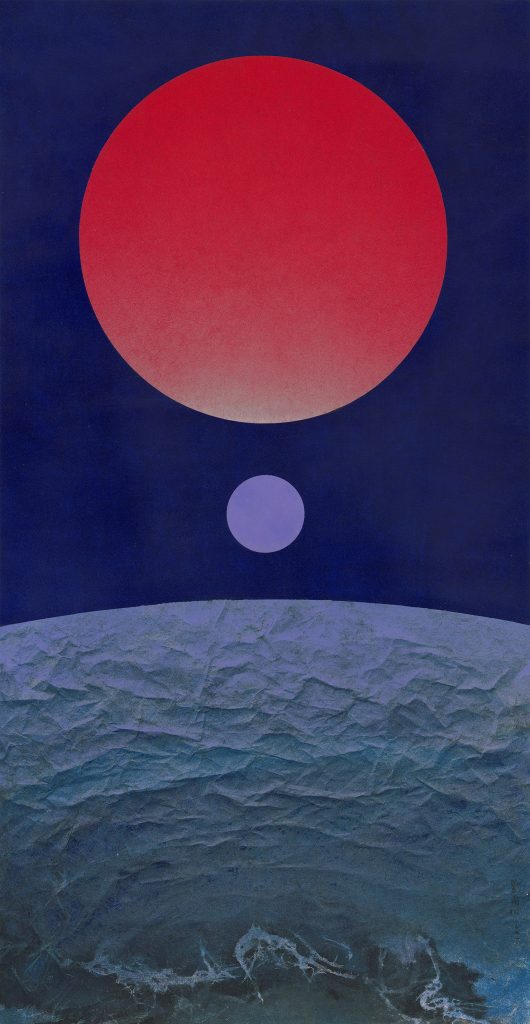

Liu Kuo-sung. The Composition of Distance no.15. 1971. Ink and colour on paper, 111.5 x 57.5 cm. Gift of The Liu Kuo-sung Foundation. Collection of National Gallery Singapore

The exhibition also allows us to explore Liu Kuo-Sung’s personal interests and their manifestation in his art. In the section titled “Which is Earth?”, we’re bound to witness how the 1968 moon landing inspired Liu to drastically alter his work, incorporating circular forms and geometric shapes that introduced an unpredictable twist in his art for a time. This pattern reemerged when Liu’s fascination with the Tibetan mountains during a promotional tour inspired him to create a long-running series of Tibetan mountain paintings, a project spanning nearly four decades.

Installation view, Liu Kuo-sung: Experimentation as Method. National Gallery Singapore 2023. Image credit: Joseph Nair, Memphis West Pictures

‘Liu Kuo Sung: Experimentation as Method’ highlights the obsession, dedication, and unpredictability inherent to an artist’s journey. This complexity is what renders humans, particularly artists, intriguing. Our life experiences and psychological depths imbue our creations with a richness and dynamism not yet achievable by AI in art. At least for now.

Liu Kuo-sung in the Gallery. Image credit: National Gallery of Singapore

As Liu Kuo-Sung continues his artistic endeavors into his ninth decade, it remains to be seen whether new alterations or obsessions will emerge in this era. Nonetheless, he appears content. In an interview, he remarked, “In the past, the Chinese learned Western painting. Now it’s the reverse.” Perhaps it’s time not only for the West, but for all humanity to learn from this human method before fully embracing the AI era – this exhibition serves as an ideal gateway to that understanding.

–

“Liu Kuo-sung: Experimentation as Method” will be exhibited from 13 January to 25 February 2024 at National Gallery Singapore, Level 4 Gallery, and Wu Guanzhong Gallery.

General Admission (free for Singapore Citizens and Permanent Residents) applies.