When We Are All Dead Inside, Maybe It’s Time to Mourn the Living

In this Open Column submission, Asiila Kamilia jots down the key in making peace with unspoken goodbyes, and dealing with “ambiguous loss,” or the departures of the living.

Words by Whiteboard Journal

When someone dies, there is an odd comfort in performing the regular rituals commonly called “funerals”. As we dispose of the remains, either through cremation or burial, we get the closure we deserve—unlike losing someone in a plane incident or a missing person for years that he is presumed dead. Through this symbolic ritual, we can mark the passing of the dead, say some last words and bid our farewell, as well as start receiving support and consolation from others. In the whole stages of grieving, a proper closure serves as one of the keys to attain acceptance. Strange as it may sound, a clear death and closure can be a good start of grieving and will hopefully ease the long road to healing and recovery. Of course, grieving over the loved ones may never end, but you will get to achieve a great deal of acceptance and be able to let go—maybe this is what we all try to aim for. However, it is not always the case; sometimes we still lose people, even when they are still pretty much alive. So, how can you mourn the living?

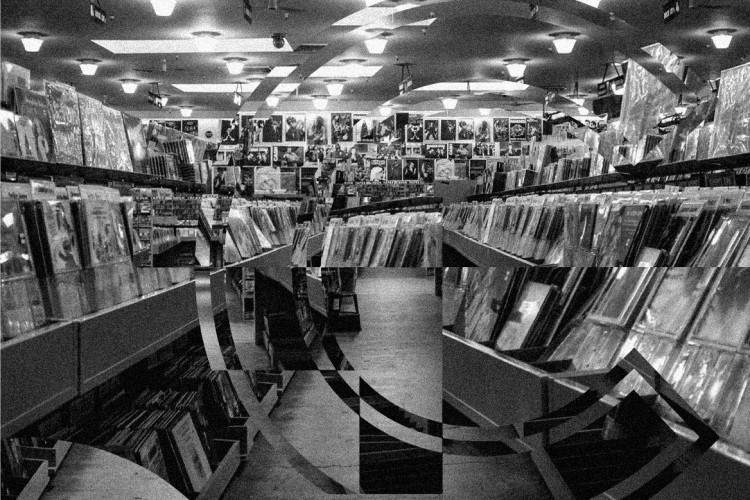

Photo courtesy of Asiila Kamilia.

Some people are physically present but psychologically absent. Pauline Boss, a researcher and theorist, calls this as a type-two ambiguous loss. The case varies from people with Alzheimer, an emotionally absent parent, to severe behavioural change of someone with addiction or having an affair. Without realizing, we have been experiencing such loss all along, but it often goes unnoticed and underestimated. I mean, look around; relationship breaks, and friendship fractures all the time. Suddenly you no longer talk to people you used to tell everything to. You long for who they used to be. Someone who used to celebrate your highs and mourn for your lows is now standing on the far side of the road, sometimes gone completely. Your muscle memory remembers his name because he used to always be there despite time and distance. The urge to call him when something happens is real because he had always been your 911 but the last time you talked was awkward. He does not take care of you anymore.

You want to tell him how happy you are now because he used to witness every catastrophic moment in your life, but he changed his number. There is so much to say but the sign on his back tells you to go. The absence of support and affection and mere existence that lasts for years forces us to shut the door and say, “he is dead to me.” You are not even sure if there ever was a door.

Sometimes it is over for them, but not for you, and at times, what seems to be a fair distance to them feels too far for you.

How do you say goodbye to that person? He is still there; alive and breathing. You can see him achieving many things. Once in a while, you hear him having some workplace issues. It is a bittersweet feeling because both of you are growing and thriving, but none of you exists in each other’s world anymore. You can never get the chance to witness his milestones anymore, so you clap in silence and smile from afar because you will not be there on their happy days and will remain absent on his rainy days as well. You are both helpless and hopeless. Then you start to feel this strange loss, fused with complicated rage and unanswered questions. Your convoluted mind begins to list all kinds of loss you have and will experience; the loss of being able to simply talk and share, the loss of fond emotional connection, the loss of mindless and fun midnight talks, the loss of weekend brunch, the loss of listening to some music and singing along together. The loss occurs gradually and maybe this is why it hurts the most. It is always one loss after the other and each loss is paralyzing.

Photo courtesy of Asiila Kamilia.

Dealing with ambiguous loss is hard as we live in a society that constantly rummages for answers, where unanswered questions are unacceptable—notwithstanding the fact that some things can be uncertain—and some other things are just plain mystery. It is difficult for us to digest and accept that people’s decision to stay will never be ours to make, regardless of how hard we try to mend the relationship. People always come and go, and we will never know how long they are going to stay. We can never know for sure if they are coming back or if they even want to come back for that matter. Even if there ever comes a day when they come back, things will never go back as they used to be before they left. This uncertainty results in an uncomfortable way of grieving and a sense of hopelessness, making ambiguous loss the most difficult kind of all. How are we supposed to cope with this?

Many of us know the drill already: Be productive, get busy, practice self-care, cry our hearts out, get under the sun and exercise. But for now, perhaps we can start by giving up the hope for a closure in any form—we may never get one and it is okay. Seeking solace in the comfort of a friend, long walk, and Serenity Prayer. “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” Knowing that we cannot control how people should behave or how long they should stay in our life. That we can only pull our own strings. They say life is 10% what happens to us and 90% how we react to it, so people leaving make up the painful ten percent of it. Keeping in mind that the fast-paced culture does not apply in grieving, so take time as long as we need to and be exceptionally patient with it because, similar with death and clear loss, grieving is a lifetime journey. In this case, time is both our friend and our enemy.

Photo courtesy of Asiila Kamilia.

One day, we are certain to have let go and made peace with the loss, accepting the fact that he is out of our life, but two years later we are back to square one, falling to pieces and crying at seven in the morning. Suddenly we feel like losing that person all over again. But that is okay, we will be alright because as time goes by, our body will learn and adjust to their absence. We will grow through the painful loss; we all do at the end of the day. It will pass in due course.

Maybe the key is to make peace with the uncertain grieving process too, not only with the loss of the person. Understanding and being prepared that the process is not linear, but rather in disarray, unsettling, and dialectal manner. Maybe people are like seasons. Maybe the days are numbered, after all. Maybe they are sent to us only for a specific amount of time and when it is time for them to go, it is beyond our power to make them stay. And if there is any substitute for this, it is the memory of a remnant of what once was to remember him by.

Photo courtesy of Asiila Kamilia.

Maybe it’s enough for now.