Once, after losing at a game, I got so frustrated that I just started yelling and thrashing about on my bed. Far beyond the point of cogent language, I sputtered gibberish while flexing every voluntary muscle in my body. In the process my leg cramped badly, just as I tottered and fell into the space between my bed and the wall. Trapped upside-down like a turtle and writhing – half from frustration, half from cramp pain, and half from humiliation – I couldn’t help but start laughing. This is probably my most embarrassing moment ever. Thank goodness no one ever found out about it…

People play games to have fun. But at what point in the story above was I enjoying myself? On my 14th consecutive failure in the game? Or maybe my 21st? Did the “fun” kick in after I fell off my bed? I can say for certain that the leg cramp was about as fun as legs cramps usually are: not very. And yet, when I recall this experience – with the benefit of hindsight – I would say that it, and the game that elicited the response, were unquestionably fun.

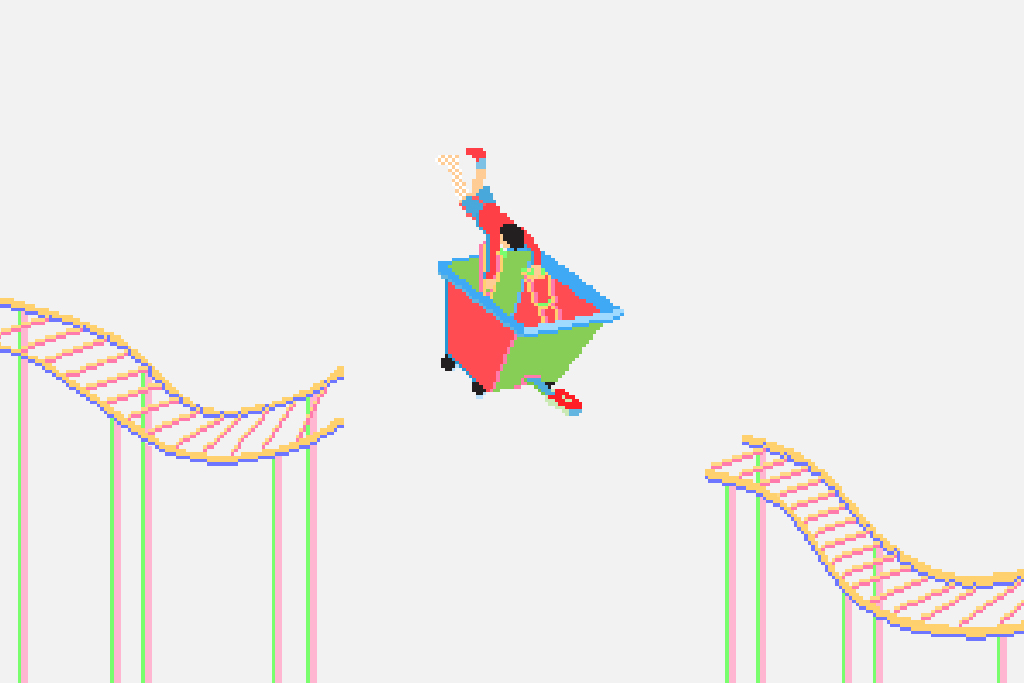

Perhaps this tells you something about my perverse sense of enjoyment. But more likely (I hope) it says something about the nature of how we enjoy ourselves. Fun, after all, is not an objective quantity, but a subjective experience of our brain. Consider a roller coaster ride. There are many individual emotions and sensations that comprise the overall experience: anticipation as the coaster climbs the initial slope, fear and elation as you plunge downwards, and finally relief for having survived the whole thing. Now, I ask you if you had a fun time. There is no single moment that you would identify as the “fun point” in the ride, but you construct a narrative that concludes with “Ya, it was great!” or “Nah, it was boring.”

Even the answer to the question “Are you having fun?” – despite its grammatical construction – is a product of a cognitive narrative. Unless you love hearing the sound of your own voice, the act of answering a question itself is not enjoyable. When you answer in the affirmative, you are really saying, “Yes, I’ve been enjoying myself up until this point, and I expect to continue having fun for the foreseeable future.” Fun, you might say, is in the brain of the experiencer.

Since becoming a gamer I have subjected myself to some horrific trials. Umihara Kawase is a series about a young girl who uses an elastic fishing rod to navigate surreal dreamscapes filled with giant fish. I really got into the latest entry, which will soon be the first to get an English release when it comes out later this year under the title Yumi’s Odd Odyssey. In addition to its wacky premise, the game is known for crushing difficultly, thankfully accompanied by a deep and rewarding movement system. The last boss took me over 100 attempts, spanning multiple hours-long play sessions. If you had approached me during any one of those tries you would not even think to ask if I was having fun after seeing my expression change from deep concentration to disappoint boarding on hopelessness (especially around attempt 80 or so…that was a rough patch.)

This does not mean that games are all about challenge, however. Cow Clicker is a famous social experiment by Ian Bogost, a game developer (and researcher) known for his wacky creations. The game, which consists of little more than clicking on various types of cartoon cows, was conceived as parody and commentary on the mindless state of Facebook games. Ironically, it turned out to be a huge hit; at its zenith thousands of players seriously engaged with the game. I would be harsher in my condemnation of this phenomenon if I myself had not gotten wrapped up by a similar game. Cookie Clicker is about…I think you already know what it is about. The point is, although these games begin with a simple premise, by layering on complexity (different types of cows, rewards for certain goals, stat tracking, etc.) and meta-goals (competing with friends), gamers are able to derive some satisfaction from them. Or perhaps we just convince ourselves we do; it really does not matter. Like all types of fun, our brains construct a narrative that labels our experience as “worthwhile.” And when you have just spent 40 minutes clicking virtual cookies, your brain will be working overtime. Trust me.

When we really start to explore the topic, “fun” may not be the best word to describe the complex cognitive narratives we weave around our gaming experiences. It certainly seems odd that this single concept of fun is positioned as the be-all-end-all of video games, when we expect such a diverse palette of emotions from novels, books, or theatre. To borrow terminology from those media, there are certainly feel-good games to get you through a rainy day, like a nice romantic comedy. But the elation of clearing Umihara Kawase was more akin to catharsis. As I discussed in my previous article on choice, there are even some games that cause us to feel guilt over our decisions; again this would not fit out typical definition of “fun.”

Next time you see someone with a controller in their hand, instead of simply asking them if they are having fun, consider a more open ended question. What are they feeling? And if you see someone writhing on the floor with a leg cramp…help them. Come on, I shouldn’t have to tell you that.