Is the Label of Being Religious or Not Really What Matters in the End?

In this Open Column submission, Gitasya Ananda Murti wrote a short story that tells of two inmates exploring the profound connections between belief and skepticism, and discovering that the lines separating faith and doubt are not as clear-cut as they once believed.

Words by Whiteboard Journal

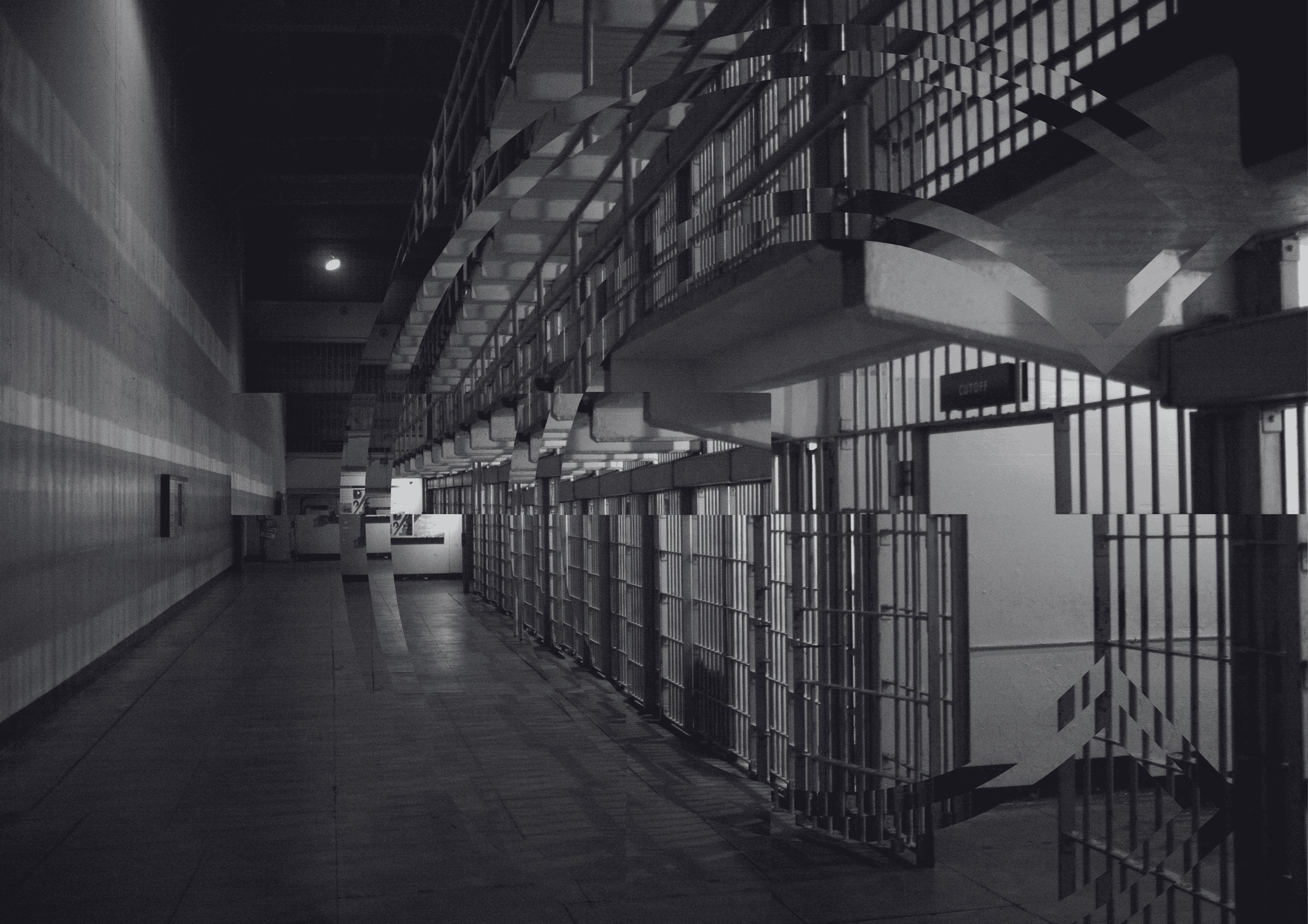

In a place of confinement—a prison—two men, separated by cold stone walls, find themselves in conversation. But this isn’t a story about bars and chains, nor is it about crime and punishment. It’s about something far less tangible yet equally binding: belief. One is religious, the other an atheist. As they speak, they’ll find that the line between faith and doubt is thinner than either of them imagined.

In the dead of night, the only sound was the slow shuffle of the prison guard’s boots as he made his rounds. The cells were dark, except for the thin shaft of moonlight sneaking through the high windows, casting shadows that twisted on the cold, damp floor.

“Lights out in five minutes,” the guard grunted, banging his baton against the bars of each cell.

Two men, separated by thick concrete walls, lay on their cots, staring at the ceiling, lost in their own thoughts.

“I hate this silence,” the prisoner in Cell 4 said, his voice low and tired, cutting through the stillness. “Makes me feel like I’m already dead.”

In Cell 5, the man on the other side chuckled softly. “Being dead’s not so bad. You get used to it.”

A pause. The soft hum of electric lights going out one by one echoed through the block.

“You read that Bible I sent you yet?” the prisoner in Cell 4 asked, his voice softer now, almost hopeful.

“No,” came the quick reply from Cell 5.

“Why not?”

A sigh, the kind that carried years of frustration. “Because I don’t believe in fairy tales. I’ve been praying my whole life. Ain’t nothing ever answered back.”

Silence again. The weight of unanswered prayers hung between them like a thick fog.

“You gotta believe in something,” said the man in Cell 4, holding the small, worn Bible to his chest like it was his last lifeline. “Even here, even in this hellhole, there’s got to be something bigger than us, something that gives all this suffering a meaning.”

From the other side of the wall, the prisoner in Cell 5 shifted, his footsteps echoing softly as metal scraped against concrete. He moved to the bars, pressing his forehead against the cold steel.

“Belief,” he said, quieter this time, more contemplative than before. “Maybe it’s not just about God. It’s about what connects us to the mystery of it all. The way we try to make sense of this chaos. You call it faith, I call it wonder.”

Without pausing, he continued, “look, I don’t need to call it God to be moved by something greater. Have you ever really stared at the night sky? Felt how small you are in it? That’s something. It might not have a name, but it’s real.”

The man in Cell 4 gripped his Bible, his gaze softening as he listened. “So, you’re saying… you feel connected to something, even without faith?”

“Exactly.” The prisoner in Cell 5’s voice quieted, his tone reflective. “I don’t pray, but every time I look out at the stars or feel the wind move through these bars, it’s like I’m part of something bigger. It’s not faith, but it’s connection. It’s… spiritual.”

A pause lingered between them.

“We’re all connected, in some way. To each other, to the universe. Even the smallest things—the way life keeps going even when we’re stuck in here, or the sound of your voice coming through this wall when I thought I was alone.”

He paused again, letting the moment breathe.

“Atheists can be spiritual too.”

“It’s about recognizing those moments of awe, where you realize you’re part of something far beyond yourself. Albert Einstein called it ‘Cosmic Religion’—standing in the middle of this complexity, knowing we’re just a piece of something much bigger.”

For the first time, the man in Cell 4 felt a shift—not in his beliefs, but in his understanding. “I guess, in the end, we’re both looking at the same thing… just from different sides of the wall.”

“The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious,” the prisoner in Cell 5 continued, his voice softening. “Mystery is the deepest emotional experience we can feel. It’s the intersection between true art and true science. Those who can’t experience it, who’ve lost their wonder, they’re as good as dead.”

“That’s… poetic,” the man in Cell 4 said.

“It’s reality,” the other man replied. “Religion, spirituality, whatever you call it—it’s born from that same experience. From the mystery. It’s what makes us look up at the stars and question why we’re here, even if we don’t believe in some higher power. It’s why we marvel at the microscopic threads that make a plant grow or at how those same threads form limestone cliffs from the bones of dead sea creatures.”

“And that’s why atheists say they’re spiritual?” Cell 4 asked, curiosity creeping into his voice.

“Exactly. We’re in awe of how cyanobacteria transformed into multicellular organisms, how that gave rise to fish, to plants, to mammals—to us. We’re stunned by how humans evolved, how we went from fighting disease and hunger to landing on the Moon and sending probes to other planets. That’s not nothing, my friend. That’s awe. That’s a kind of religion in itself.”

He paused, gathering his thoughts. “We’re just a collection of water, calcium, and molecules, right?” His voice rose slightly, energized by the conversation. “But that’s what makes it all so incredible, don’t you see? We’re simple ingredients, lifeless on their own, but together, we become something extraordinary. You and me—two lumps of atoms, somehow alive, thinking, feeling.”

He leaned against the bars, feeling the weight of his words. “Some people think that makes life less special, like we’re just a bunch of dancing molecules, fleeting and fragile. But I think it’s the opposite. What could be more miraculous than lifeless matter coming together to form hearts that beat, minds that wonder about the stars, hands that reach out even through these damn bars?”

The man in Cell 4 shifted on his cot, staring at the concrete wall between them, the Bible suddenly feeling heavier in his hands. “And what do you think that makes us?” he asked, his voice barely a whisper.

“It makes us part of something beautiful, man. Not just pieces of matter. Something more. A symphony, a pattern too big to see. It’s the bonds we create, the connections we share—that’s where the meaning is.”

The man in Cell 4 shifted on his cot, the Bible still heavy in his hands. ‘You make it sound like we’re not that different. Atheists and theists.’

“We’re really not,” the prisoner in Cell 5 replied. “The difference is in interpretation. I know you’re frustrated with the church for rejecting science and punishing people like Galileo. That frustration reflects a common struggle—trying to find meaning in a world where it feels like knowledge and belief are in conflict. But that frustration is rooted in a specific interpretation of religion. You see faith as something that limits knowledge, but many of us believe that faith and science can coexist.”

Cell 4 smiled faintly in the dark. “You’re not wrong.

And I get it, you’re frustrated with the idea of a God who only cares about reward and punishment,” Cell 5 continued. “But that’s just one way to look at it. The God you argue against isn’t a definitive being—it’s a concept shaped by human perceptions and understanding of God itself.

Remember the saying: ‘The map is not the territory’? It means that our interpretations don’t capture the full picture. Even within the same religion, people can see and understand God in vastly different ways.”

The man in Cell 4 exhaled slowly. “So what happens when we all end up in the same place? When we reach the ‘territory?’”

“Then there’s nothing left to argue about,” the prisoner in Cell 5 said with a soft chuckle. “The arguments were always about the map. In the end, we’re just travelers with different maps, trying to find our way. We stop arguing because, at the end of the road, we all see the same thing.”

The man in Cell 4 lay back on his cot, letting the weight of the words sink in. “I see myself in you,” he said after a moment. “We both agree that existence doesn’t pick a side. Theists, atheists… it’s the same. And you know what? Your perspective actually makes me believe in God more. It makes me feel that God’s everywhere, in everything.”

The prisoner in Cell 5 smiled, though Cell 4 couldn’t see it. “As an atheist, I say that spirituality is just admitting that we don’t always know. And as a theist, you admit the same. It’s the unknown that connects us. So if we’re talking about the same mystery, what really separates us?”

Another long pause.

“I guess we spend so much time and energy arguing over things that don’t really matter,” the man in Cell 4 said, his voice thoughtful now. “When the truth is simple.”

“Exactly,” the prisoner in Cell 5 agreed. “We’re all searching for proof, for answers. But there are different levels to that desire.”

It’s time we move beyond just debating and throwing theories around.

There was a silence, not of uncertainty, but of agreement.

“We’re all part of the same cosmos,” Cell 5 concluded. “With different maps, sure. Some believe in a god, some don’t. But in the end, that doesn’t matter. What matters is that we’re all here, together. We share the same journey, and that’s all we need.”

And as the prison guard’s boots clacked down the hallway again, both men—one with belief, one without—lay in the dark, connected by the same vast unknown, a strange kind of peace settling over them both.