Europe Is Not All Shining Shimmering Splendid: Taking a Look as an Outsider

In this open column submission, Qanissa Aghara shares the things she saw in Europe through the eyes of a foreigner (an exchange student, to be precise), and how the widely romanticized impression of Europe starts to unravel one-by-one through this photo-essay of hers.

Words by Whiteboard Journal

Coming from a middle-class family background, I considered my childhood to be surrounded by ‘Western’ media and consumer goods (e.g. dolls, CD-ROM video games, late night Hollywood box offices, fictions, etc.). It was also a common sight to have ‘blasteran’ (multi–racial) actors and actresses gracing the television screen; with perceivably distinct visual features—sharp noses, thin lips, bright deep-set eyes, fair skin—than the more common Southeast Asian features that I have. Personally, the media was and is still an influential factor that shaped my mentality.

Alongside all these, my father was working as an engineer in a private multinational company for more than a decade. Through this affiliation, he had several chances to be enrolled in workshops and conferences abroad. He always took several photos when visiting other countries—the composition usually consisted of him standing in a distance near national landmarks—his photos consistently managed to capture wide horizons and the colossal settings of each landmark. One notable example is his photo in front of the great Eiffel Tower glistening with the warmth of a sunray, between neatly mowed grass fields. He also often expressed contentment towards European public systems. When he would come to Indonesia, I’d hear him complain frequently about how Indonesia is very messy—systematically, culturally, and socio-politically. All in all, studying and perhaps living abroad is considered an achievement in the environment in which I grew up, this sentiment is usually being inferred through our daily conversations.

Maastricht, September 2, 2022 (Courtesy of Qanissa Aghara)

By fate and absolute luck, a few months ago I was given the opportunity to temporarily live in Maastricht, Netherlands for half a year. Since the very beginning of the departure, questions had filled my mind as I perceived Europe with quite a stereotypical and romanticized point of view. Was it actually an ideal place at all? The beacon of modern civilization? In this column, I would like to share my retrospective view regarding several bits of Europe through my camera lens and some notes–inseparable from biases and memory inaccuracies. As I’m writing, I’m also looking back on some captured moments. It made me realize the power of photography as a method of representation. Photos as outcomes, hold some degree of persuasion, to view something through a certain lens and point of view. Likewise, with the language I chose to write with. Despite being a native Indonesian speaker, I decided to write in English as a vessel to communicate the ideas more broadly; by using “Universal” Language, as it is commonly referred to; as a way to deliver criticism to language hegemony—which reflects other hegemonies in various aspects of life, that are seen as normal and typical. First World-Third World? Core-Periphery?

Undeniably, when I was there I got to enjoy free-flowing tap water, walkable environments, and an established waste management system in the places where I stayed and traveled. Everything on the surface level was pretty similar to what my father had conveyed—Organized. Large roads without many vehicles (except for bicycles and buses) are well maintained without any holes. Parks all over the town, well-planned spaces, and appropriate signage. Yet at the same time, the weather was quite unbearable for me. Having lived in a tropical country my whole life, it was piercingly cold and windy.

Trash and open field, September 2, 2022 (Courtesy of Qanissa Aghara)

It’s quite surprising for me to witness how weather dominantly influenced the way I carried out my daily activities, including studying, socializing, and doing groceries—three activities that have become inseparable from my life there for six months. I became a more prompt and orderly person, the self-checkout cashier showed me how consumer accountability was taken to another level, the ambitious and more active class environments, cultural and language barriers that can either be an advantage or an obstacle, and just the overall tendencies of how most people carry out their life. Everything was tactical and on point, learning for learning; socializing for socializing; partying for partying—All appeared to be in place, except for some trash seen surrounding the garbage dump below. They seem to have been left out, since those compartments didn’t seem to allow each abandoned goods to fit, or perhaps someone just gave up on public rules and customary procedures. (re: categorizing waste)

Garbage dump near Brusselsepoort, September 2, 2022 (Courtesy of Qanissa Aghara)

During my brief stay, the impacts of the Russian-Ukraine war weren’t as severe and visible, if compared to other countries that were closer to the Russian or Ukrainian borders. Yet signs of energy crisis and inflation were quite inescapable. I wasn’t someone who keeps up with the local news, but the forced closure of one of the most visited learning spaces did not slip from my attention. It was winter, days were short and energy demand was heightening due to the temperature drop. Due to energy scarcity and large operational costs, the public, free learning space with various rooms, had to close until the end of the year. That fact was quite saddening at least for me, since I didn’t know many other study space options—going to that learning space was one of the very few variations on my chores, apart from going to a packed campus and dormitory, especially in winter when standing outside was quite a discomfort on its own.

Maastricht Sustainability Hub, October 1, 2022 (Courtesy of Qanissa Aghara)

The crisis doesn’t stop there, residents and diasporas in the Netherlands might recognize housing scarcity as ordinary. It has become somewhat commonplace, and despite the influx of international students and workers, there wasn’t enough space to accommodate newcomers. From several conversations, I have heard that landlords can be viciously ‘picky’ over choosing their tenants. There were also several scams that involved uninhabitable and unkempt spaces being rented out. Besides, the nature of a plot of land being owned and passed down through generations doesn’t make it easier to bear the crisis. This crisis was followed by competitively high and ridiculous costs of rooms and sublets. It’s quite common for international students or new residents to live in another city, having to commute across cities or even countries daily, or to live temporarily in so-called student hotels.

Abandoned junks underneath a bridge in Berlin, December 18, 2022 (Courtesy of Qanissa Aghara)

Apart from the several problems mentioned above, European countries have their particular attractiveness with the status and affiliation of the European Union (EU). For example, the ownership of a Schengen Visa allows me (a Southeast Asian) to visit other EU countries without having to face unimaginable administrative matters—apart from the long history of migration, accessibility, and bureaucratic power that have retained the status of European countries as international destinations. Even some cities are referred to as more international than the others, including Maastricht and the Netherlands in general. On a day-to-day basis, I had little trouble communicating since most people are fluent in English. In fact, I wasn’t required to speak Dutch at all, thus finding a community and place to belong was more bearable with less of a language barrier. This is certainly quite attractive for newcomers, and migrating residents (apart from the difficulty of finding a place to live).

View of the dormitory parking lot at night, August 26 2022 (Courtesy of Qanissa Aghara)

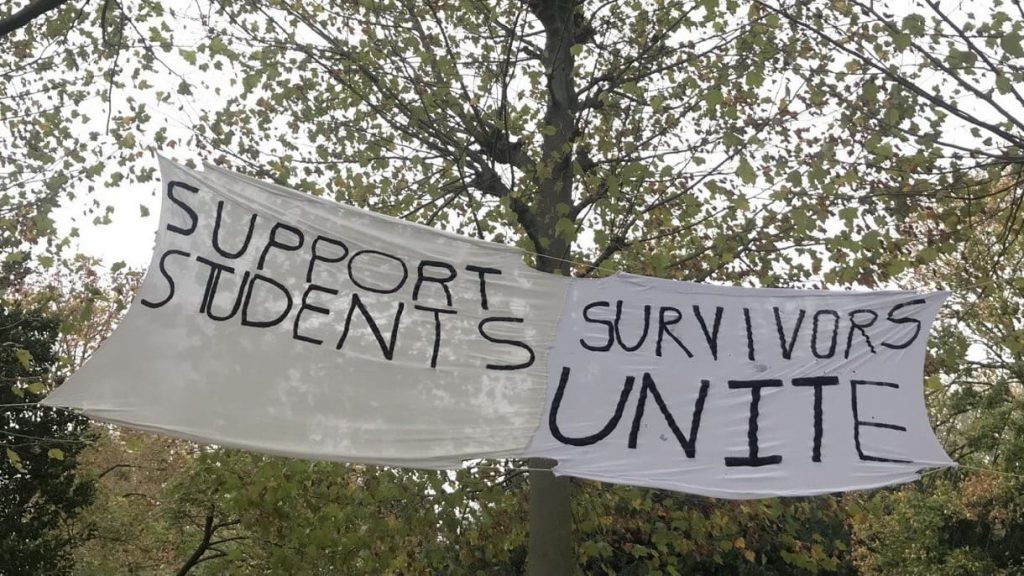

With students coming mostly from all over Europe and ‘Global-North’ countries—that were famed with ‘higher’ living standards by all-’other’-sides of the world—I expected that the policies and stances would be more welcoming and catered towards students’ welfare. However during my stay, there was a sexual violence misconduct accusation in the educational institution, the news of which quickly spread among students. The place where I studied was also known for having vocal students that carried several protests and demonstrations from time to time; reports were filed, huge banners were put up, and silent protests were conducted in front of the faculty building for several weeks. But unfortunately, the institution did not resolve the issue in a satisfactory way, the victims weren’t granted their justice, and talk of the issue eventually died down, although I still hope that it has actually been resolved by now.

Banner by students’ grassroot organization, November 7 2022 (Courtesy of Qanissa Aghara)

In relation to study discipline, I happened to be a visual arts student, which basically has a Western-oriented curriculum; all those topsy-turvy notions of art. Europe is famous for its museums and artifact conservation practices, and definitely seen as the place where modern art flourishes. The institution and practice behind the Museum are definitely unique since its history is inseparable from the industrial revolution, the era of Enlightenment, overseas journeys, and… colonization (of course!). Prior to witnessing the actual European museum setting, I already imagined drowning myself in numerous classical works of art–sculptures, paintings, etc., but the chance of visiting the Louvre in Paris, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, for instance, made me realize how it is impossible for those institutions to stand on their own; having prestigious status without the support of their collections—many of which came from different parts of the world, whether taken as a sample, souvenirs, war loot, or conceived through colonial force. Of course, we currently live in an age that enables multilateral cooperation between countries in the domain of cultural heritage—Therefore, questions of repatriation and ethical collection practice might be better accommodated. But apart from all that, the history of artifacts displacement—that for once might be meaningful and sacred to certain communities—couldn’t be erased.

Best kapsalon in entire Maastricht ‘McDonerBox’, September 16 2022 (Courtesy of Qanissa Aghara)

For my temporary time spent in Europe, I lived as a student in places with a higher currency rate than my home country. There were no other options than to cut off some expenses and save up some money. One of the easiest ways is to cut off food spending. For most of my stay and visits, I usually got the cheapest food options—and it’s usually offered by migrant-owned businesses. Not only accessible, but the portions were also enormous, it was a mouthful of flavor bombs, and they succeeded in conveying diversity through another point of view, a hearty one. Likewise with tourist attractions, usually souvenir stands around these attractions were owned by migrants, catering to the tourist preference, based on each of the landmarks. All the exposure to museums, restaurants, and souvenir stalls made me realize how these international cities weren’t built off of a homogenous community, but a heterogenous one; various people with varying backgrounds coexisting; supporting each institution.

Eiffel Miniatures, Paris, October 25 2022 (Courtesy of Qanissa Aghara)

However, despite heterogeneity that was deeply rooted in the development and maintenance of these international cities, there’s an increasing case of pushback issues. Along with the Russian-Ukraine turmoil, pushback issues appeared more frequently in the news, online media, classes, and daily conversations. Europe is accused of doing more illegal pushbacks as far as dumping refugees in the sea; despite the rights of refugees as asylum seekers to gain protection and shelter. Before coming to Europe, I lacked knowledge about refugee and migration issues, but since I arrived in Europe the discourse about borders was in every corner—again, considering how Europe was also built by the history of diasporic displacements. One of the highlights was when I went to an exhibition composed of participating artists who are all migrants–regularly and irregularly. Many of the works presented migrant experiences, living on the thin thread of safety. This exhibition was held in an abandoned underground tunnel that used to be a NATO headquarters. Several performances showed participant’s faces, yet there were also video works that hid the artist’s actual identity, as a safety measure. This exhibition conveyed first-hand migrant experiences that proved once again if the idea of total safety is utopian wherever one sets foot.

Main street in Rome, January 1 2023 (Courtesy of Qanissa Aghara)

This article wasn’t made to purposefully paint things badly. Rather I wanted to balance the pre-existing discourses that romanticize Europe; deeming it as ideal and desirable—when actually their status and prestige were excerpted from years of hegemony through colonialism. After all, there were never any actual black-and-white views in this world. Any views are valid, whether to see Europe through the sight of its landmarks and architectural mystique or to remember the ‘magical’ reek of urine in the streets, piles of rubbish in abandoned culverts, tourist scams, and unfamiliar times abroad. Currently, for me, Europe isn’t how I saw it through my father’s film camera. It’s yet another imperfect place on this Earth that gained prestige, inseparable from risks and crises, with slightly better public systems, and well-preserved architecture.