A Year After Reformasi Dikorupsi Movement

Column: In this Column submission, Aldo Marchiano Kaligis reflects on the events of Reformasi Dikorupsi and sees the movement’s efforts to negotiate unjust social contract deeply rooted in Indonesia’s political practices.

Words by Whiteboard Journal

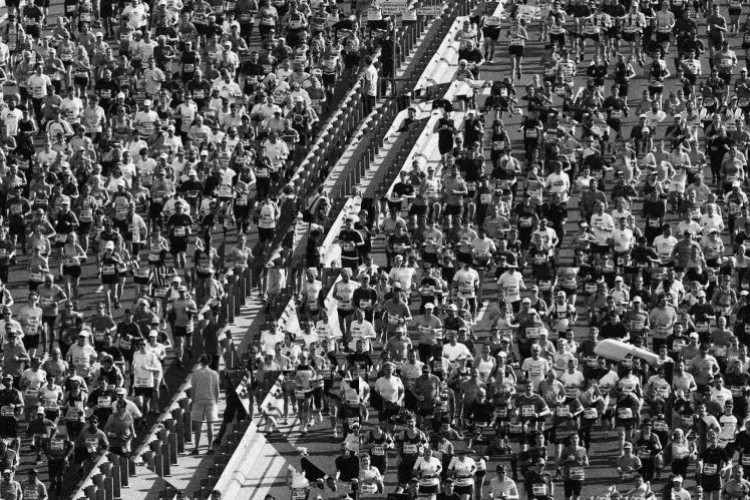

September 2019, Indonesia witnessed the most massive mass protests since the Reform movement back in 1998. Students, labor unions, activists, and other civilian elements in different cities in Indonesia took to the streets from 20 to 30 September 2019 to express their dissatisfaction regarding how the country is being run. They demanded the strengthening of the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), the legalization of the Anti-Sexual Violence bill, the end of military occupation in Papua and West Papua provinces, and investigation of human rights abuses by the police, among others. The people reiterated the importance for the government to fulfill the Reform 1998 agendas, hoping that the 2019 protests could remind the state about the unfulfilled promises and bring about a similar impact as its predecessor in holding the government accountable. The protests were widely known as the Reformasi Dikorupsi movement.

Many were hopeful toward the movement. An air of optimism clouded the students who were once again labeling themselves as the agents for change. Labour unions sang the songs of revolutions, hoping for a better working condition and put an end to the exploitative nature of contemporary businesses. Activists reminisce about their past victories in toppling down Soeharto’s authoritarian regime when they saw the Reformasi Dikorupsi movement. The nation was hopeful that the massive protests could finally end the unjust state-citizens social contract deeply rooted in Indonesia’s political practices.

Many people believe that such a political event means that there is a realization amongst the people that the government cannot carry on its duty to respect human rights. Such a realization, hence, pressure the state to renegotiate an alternative social and political practice. Unfortunately, shreds of evidence have shown that the system could not be easily broken. Instead, through the continuing oppression towards civil society, the state can preserve the status quo and prove that the state-citizens relationship is malleably resilient. This article will argue that the movement failed to renegotiate, leave alone break, such an unjust social contract on the face of a brazen government.

At least three factors influence the lack of change in Indonesia’s social contract. Firstly, the government is more than willing to use excessive force when faced with criticisms. Secondly, the state’s ability to frame vulnerability through the media obstructs the public’s imagined alternative ways of doing politics. Lastly, the sustained alienation of civil society in the decision-making process further shuts the opportunity for co-production.

One need not look far from the protests to find evidence of excessive use of force. On one of the days of the protests, 24 September 2019 to be exact, the police used water cannons and tear gas to disperse the mass gathering in front of the Parliament building, Jakarta. Afterward, the police started to hunt down and arbitrarily arrest protestors, leaving many people shocked, wounded, and missing. On 26 September 2019, at least two students were killed due to beatings and gunshot wounds in Kendari, Southeast Sulawesi. Four days later, water cannons and tear gas were again used to push back protestors in Jakarta. The police forces even surrounded the Atmajaya University building, a designated first-aid area for exhausted or wounded protesters, threatening many civilians’ lives.

In justifying such brutality, the government framed as if some protesters deserved to be forcefully handled. On 25 September 2019, the Chief of West Jakarta Metro Police, Hengki Haryadi, held a press conference where he differentiates between protestors and rioters. For Hengki, the protestors were the ones who were peacefully expressing their demands. In contrast, rioters were the ones who instigated the violence. Similar framing was also used by the Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal, and Security Affairs, Wiranto, on a press conference he organized on 26 September 2019. Such framing implies two points: firstly, the excessive use of force was merely a response to rioters’ violence. Secondly, some people deserved to be brutally handled by the security forces; there are lives more important than others.

The state was also reluctant to facilitate public demand in the first place. Ministry of Research and Technology, Mohammad Natsir, made a public statement on 26 September 2019, saying that the protestors did not even understand the substance of their demands. Furthermore, in a meeting with President Joko Widodo on that day, Natsir noted that the president urged the student protesters to stop taking the streets and immediately get back to their classes. As a result, for instance, the revision of the Corruption Eradication Commission Law rejected by the people due to its potential to weaken KPK was eventually accepted by the president and came into force on 17 October 2019.

The shameless strategies used by the state continue until today. The government is even more relentless in using excessive force to silence any forms of grassroots resistance, such as the continued joint operations between the military and the police in Papua and West Papua province. Political framings toward activists and civilians flourish both through traditional and social media platforms. The government even has a systematic cyberattacks initiative to sway the public opinion on Papuan-related issues. The public is barricaded from participating in the decision-making process, as shown by the business owners-led formulation of the Omnibus bill. These instances prove that the Reformasi Dikorupsi movement failed to renegotiate the unjust social contracts when faced with the oppressive state’s response.

From the people’s perspectives, one of the immediate impacts of the aforementioned government strategies is the lack of follow up protests. The people are faced with the immediate threat of losing their lives shall they organize another protest. Even if they may organize another movement, the people feared that it would only lead to another unsuccessful attempt to renegotiate the existing social contracts. Furthermore, the people not only need to face menaces in real life, but they would also be stigmatized as rioters due to the government’s framing ability and power. Bear in mind that the framing is not a one-off moment: if done through social media platforms, it can also lead to cyberattacks, such as doxing, that the people will experience digitally. To make matters worse, cyberattacks could potentially transform into real-life threats such as intimidation, attacks, or even affecting one’s mental and physical health conditions.

However, this article is not a call of surrender. Far from it, the piece is a reminder that new resistance strategies and solidarity need to be explored and immediately executed since the government has many flaws. Different options, resulting in a variety of impacts, are still available for the people to utilize. Stopping now will only lead to the government exercising further unchecked politics and closing the door for renegotiating the state-citizens relationship. More severely, however, we are consciously (or unconsciously) putting the voiceless to remain voiceless in the foreseeable future.