Revisiting MBTI Through Carl Jung’s Point of View

In this open column submission, Tsania Mahrani shares her research behind the popular personality test through the lens of Jungian Analytical Psychology.

Words by Whiteboard Journal

Perhaps one of the ways we can understand the intangibility of the process in which consciousness took place, we can learn a thing or two from the framework in which Jungian Typology was built upon. In his book ”Energies and Patterns in Psychological Type”, John Beebe integrated a lifetime’s work of Jung’s Analytical Psychology and unraveled them in such a manner to give a clearer understanding of how our psyche’s consciousness gather and contemplate on the information that we receive. That is, through what is known as cognitive functions, or the eight archetypes in which Jung proposed for the first time in his book, ”Psychological Types” with additional labels that John Beebe had put together himself: Fi (Introverted Feeling) or appraising, Ti (Introverted Thinking) or defining, Ni (Introverted Intuition) or knowing, Si (Introverted Sensation) or verifying, Fe (Extraverted Feeling) or affirming, Te (Extraverted Thinking) or planning, Ne (Extraverted Intuition) or envisioning, and Se (Extraverted Sensation) or experiencing.

According to Carl Jung, these eight types of awareness i.e. how we came to know and perceive (perceiving in the Jungian sense, more on this later on) things through a conscious process, explain and construct an individual’s psychological framework. In other words, it has the power to push forward onto our psyche and become in itself, a form of consciousness. It can be seen in this way because of their nature in which they’re able to energize and develop over time – will and time being two factors that can become a part of our consciousness. With that in mind, yes, there is a kind of separation between the well of what we call unconsciousness and consciousness, but it may be more integrated and not as separable as we thought it to be before. Rather, it is perhaps through one of those two notions we can fully get a hold of the other; making it something inseparable, like a tandem in which our psyche works.

To comprehend what the eight functions are, and how they contribute to our consciousness, we must first understand what cognitive functions are. Cognitive functions are the mental processes that are present in a person regardless of the circumstances in which they currently live in. If I were to put it into an analogy, it is perhaps like a background music that keeps playing in the back of your mind and it has the power to evoke emotions and perceptions regarding the outside world, and no matter whom you’re talking to and where you’re going, it’s always present there; though, sometimes it would become more intense or less intense depending on the situation which you’re currently dealing with. When the outside world is chaotic, the noise may become less noticeable, and vice versa; but in the end, its existence will always be there, structurally unchanged. It’s also important to know that Jung divided these functions into two pairs of opposites: the evaluative functions, that is thinking and feeling and the perceptive functions of perceiving in a Jungian sense, that is sensation and intuition.

A brief explanation of these functions would be: thinking is knowing what is or fitting something into a logical framework, feeling gives you the ability to find a matter to be agreeable or not, or is it worth accepting or rejecting (a sense of morality), sensation informs you that there is something or being aware of the physical properties of the environment, and intuition — something that is harder to explain. Jung (1957) explained in his book that this function isn’t as easily defined as the others, for instance, when someone feels like he has a hunch that something unsavory is about to happen, he can’t exactly explain it in a manner which makes it logical or tangible to others, can he? So to make it more concise, Jung explained this particular function as perception via the unconscious. Thus, making it the one function that can explain the interrelated nature of our consciousness and the unconscious. To understand it better, we can use Extraverted Intuition as an example. Since Extraverted Intuition manifests itself in envisioning the future or the possibilities that could happen in the future. With this way of thinking, of course, certain properties are intangible and closer to an unconscious way of thinking (as the process of using the function automatically with little effort), and there’s the picturing and imagining said scenarios that take effort and a conscious way of thinking. In cases such as Introverted Intuition, we would experience some form of transcendence by gathering knowledge unconsciously and bring them about in a conscious manner. Like experiencing a life-changing event that made us feel an inherent sense of change and self-growth, which, in turn, makes us pave our path in life for the better (or worse).

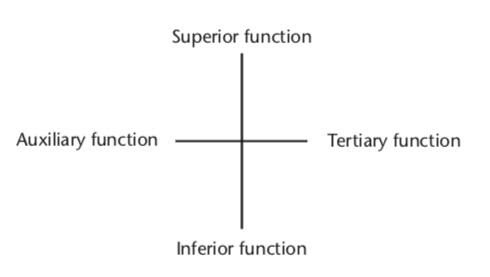

To better understand the dynamics of the four functions, let’s take a look at this:

Jung’s Hierarchy of the First Four Functions

The picture above shows how Jung would put these functions in a hierarchy that gives their roles and nature into perspective. These two axes describe the position of the person’s four functions of consciousness in relation to others (Beebe, 2017). In other words, these positions act as a form of differentiation that is qualitative rather than quantitative in nature, regarding in which a person experiences something, and how the world around them perceive it to be. And that is to say, how a person experiences something differs from the others as the result of the position in which their cognitive function lay upon in the hierarchy. For instance, a person who has Introverted Thinking as the superior function, would by default use it in a manner that is more sophisticated and intense (qualitative in nature) than another person who uses it as their inferior function. Furthermore, John Beebe explained that the vertical axis acts as the ‘spine’ of the consciousness defining the person’s conscious standpoint, and the horizontal axis acts as the ‘arms’ of consciousness since these functions are used as a means to handle the relation to the world once the individual standpoint of the person is established.

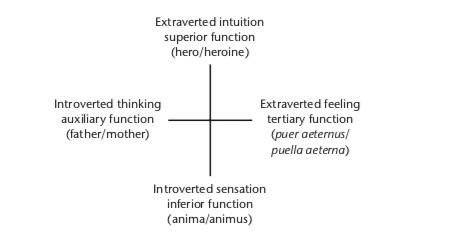

Now, to better understand the relationship of the first four functions, we can take a look at this demonstration which depicts the functions with their respective archetypes (Beebe, 2017):

John Beebe’s Version of the First Four Functions

This model asserts that if the superior function is irrational, the auxiliary will be rational and vice versa. The auxiliary function poses as the force that keeps the superior function ‘sane’ i.e. doesn’t let the Hero fly around alone burning down the enemies or it may be something which acts as the opposite i.e. pushes back the Hero so it will never do anything significant in its life. It agrees with Myers and the MBTI that if the superior function is introverted, the auxiliary will be extraverted and vice versa. This one follows a logical relationship between the four functions; since after we gather information inwardly or outwardly, we would also practice or put it in a similar manner but oppositely. Either it is to organize it, or to create something with it through a conscious process. And there’s no way that we’re doing both things, simultaneously, only outwardly or inwardly. The diagram also specifies the tertiary function as opposite in attitude to the superior. Following the Jungian tradition, the model maintains that if the superior function is rational, the inferior will likewise be rational; if the superior function is irrational, the inferior function will also be irrational. For instance, if the Hero is functional, then it can serve as the backbone for the inferior function, supporting it in such a way so that the inferior function will be able to get past its insecurities and cope with its vulnerabilities; this is possible because the two functions were formed by the same axis. The tertiary function is represented as matching the auxiliary with respect to rationality or irrationality. The model, therefore, defines two axes of consciousness, one between the superior and inferior functions of the spine, the arms will be irrational and vice versa (Beebe, 2017).

The brief explanation that Beebe brought using his hierarchy serves as a way to rationalize the process in which some individuals are considered psychologically “healthy” (if there is even such a thing, but for the sake of the argument, sure.), and why some others have more troublesome ways (according to what the majority of the population considered as the norm) of manifesting their behaviors in the cognitive function realm; it also explains why there’s no such a thing as a one size fits all personality. Each personality, despite having similar stacks to their cognitive functions, would use it in a relatively different manner. There would be some who prefer to use their stack to create something from their inner world and then packing it in such a way for the outside world to consume, and those who prefer to be present in the environment such as making apparent and immediate changes. In other words, this would also explain the process of individuation that Jung proposed, and how we make the best of our conscious abilities to perceive and process the information that we receive. With the dynamics of each of the first four functions, we can understand better why the irrationality or rationality of one function affects the other, and how each of them contributes to the nature in which the first four functions behave and manifest itself. So even though it’s true that this whole explanation is just an oversimplified version of how our consciousness works, it’s still a factor that we might want to understand better to get closer to the truth.