Photography and Jakarta with Erik Prasetya

Athina Ibrahim (A) talks with Erik Prasetya (E)

A

How did you get into photography?

E

My mother bought a camera for me to document family potraits when I was ten years old. I then was more skilled compared to her. The camera I had came without a light meter. Back then, a light meter was hard to come by. Even if we did find one, it was often damaged or broken. Thus, I committed to memorize the proper exposure for photographs. The only thing I memorized is that, if it’s on the beach, it is set to either 125 or 250, not 11. That means if it’s at darker location, it’s not 5.6.

A

You knew all the details?

E

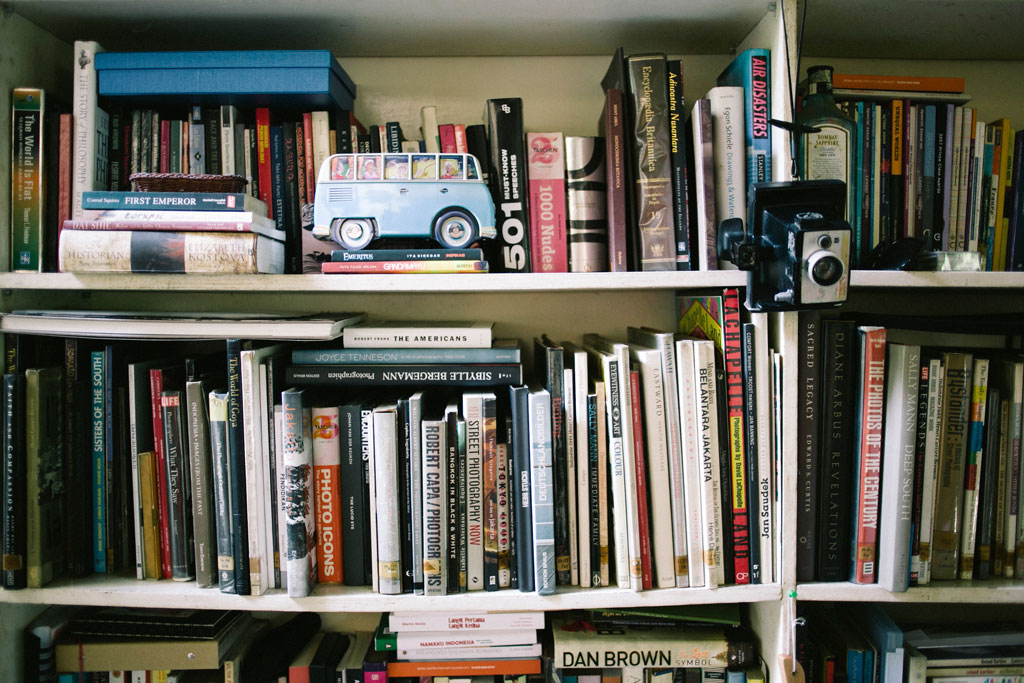

Definitely. The details were ingrained in me. I was better at handling the camera compared to my parents to the point that wherever there were events that required a photographer, I’d be the one taking pictures. Later on, I had a friend at primary school who owned a dark room. I started to learn how to develop and print pictures. I was used to developing huge prints as well. We even experimented by printing on reversal film, which was used by black and white cinema. Thus, I was exposed to photography since I was very young. However, my parents opposed it and I stopped halfway.

A

When did you decide to devote yourself to photography?

E

Once I graduated from college, I decided then on that’s what I want to do. But my background was in mining. So I decided to join the oil industry for its good pay and took up photography as hobby while working in the oilrig. However, I didn’t stay for long as I realized it wasn’t something I was interested in. I felt more gravitated towards journalism and became a contributor. Then I became aware that writing was not easy, so I dropped out. I realized that photography is an aspect of journalism I felt I could do. In my opinion, photography is not that complicated. No matter how good a photograph is, I can look at it and think, “Oh, I can do that.” But that doesn’t apply to writing. I used to look at other people’s articles and think, “The writing is great. There’s no way I could do that,” while other journalist can do it every week. If I could write like that just once a year, I’d already felt as if I am best in my field. Whereas when I looked at photos from National Geographic of all kind, no matter how difficult it looks, I was certain I can do it. The only thing I’m not confident about is knowing the techniques they employed and realized the problem lies in speed. Thus, I decided that I’d stop writing but photograph instead.

A

What do you mean when you say there is no photograph that is too difficult?

E

Well, actually it’s just an intuition. For example, there is a point when we realize, “it’s not my field but I might be able to do it if I made an effort in it.”There’s that sense, like when you are being told to be in a film, and we’d think, “There’s no way I can do it”. Yet, there are those who feel that they are able to do it as long as they give it a try. That’s the intuition that I had when I was faced with the decision to choose between writing or photography and I picked the latter. I got involved in the industry pretty late at the age of thirty in 1988. It was my first paid professional assignment. Even so, it would have been even later if I had started at 32 or 34 year old. At first, I was asked to do some research in the Asmat region of West Papua. I spent forty days taking photographs while I was actually paid to be a researcher. However, within a year I became a photography coordinator and took plenty of pictures. It was my first lesson in photography.

Was that the period where you explored photography the most?

Nope, that was the basics. That was the basics I needed to know the audience’s expectation and what it took to make a book popular. So from there, I started learning to shoot almost anything from the oddest tribes and artifacts. In the real world, there’s also modeling such as act shot, factories, and photographs of air. I have to try it all and I laid my foundations on that. Secretly, I started to feel that it was becoming too easy for me and I needed something new. In the end, I decided to shoot in black and white to produce works that feels more personal.

A

Why black and white?

E

Back then, all professional photographers used color slide film. It is a very expensive film but it was the best and produced good colors. Whenever I work with colors, I felt as if I wasn’t doing something personal, as if I was assigned to do it. Whereas black and white reminded me of my youth. When I was young, I would often shoot in black and white with a huge camera, then developed and printed the pictures all by myself. So there was that feeling to it and I decided that black and white was the way to go.

A

Is it because with black and white emotion are more distinguished?

E

I only came to that realization recently. It’s actually harder for someone who shoots in colors to shift to black and white. It’s another level of discipline. Even though I’ve already been exposed to black and white photography when I was young. In the end, I decided to choose Jakarta as the subject of my project around 1991 or 1992. That work then became known as The Banal Aesthetics of Jakarta twenty years later.

A

What vision did you have to compile a physical form of your work?

E

In the beginning, I really wanted to tell the story of Jakarta. The reasons are simple. First, it was cheap. Secondly, it was a personal project, so I didn’t have to worry about the budget, as Jakarta is my city. As I dug deeper, I started to realize something more philosophical and it was that people often photograph something exotic. They would travel out of the cities and into villages to find things they can’t find in the city. I used to shoot villages in Kalimantan and Krakatoa for money. It was an exotic approach; it was something different from what we had. However, I do not want to use such an approach. I wanted something that is as reflective as possible. Since I came from the middle class, I felt that I shouldn’t just photograph the middle class. However, if I were to photograph the lower class that still means exoticism and if I were to approach the upper class, it is much more like peeking. Thus, if I want to be reflective, I probably have to approach subjects that are in the same class I am in. As a photographer coming from the middle class, I belong neither to the lower or upper class. Probably along the line of a middle class as photographer, so I thought to myself, “If I don’t want to show something exotic, it has to come from my own class, such as my friends.” So I decided that is going to be my first approach. Afterwards, I encountered difficulty while photographing.

Let’s say I’m someone from the middle class venturing into the area of people from the lower class. It is actually another world altogether. Therefore, I can easily detect the drama in that. Drama comes from all kinds of contrasts. It is easy to see it when poor people are evicted in contrast with grand buildings. Now there is some tension in that whereas, there is no such contrast from my class. To wit, when poor people are eating at food stand with simple dishes and it appears to be appetizing, there can be tension in that image. However, as someone who is from a higher class than him or her, and drops in on McDonald’s with my friends for a meal, where is there tension going to be in that image? From there I tried to formulate another approach to it. We can’t pursue drama. There is not relevance in drama here.

A

So it’s not tension that you are after?

E

Tension creates drama. With such a high tension, it bounds to have drama.

A

Won’t the emotion be more distinguished with tensions?

E

Yes, of course, But I find that to be too easy. We all knew the formula, which lies in finding the highest tension, if you want drama. That’s it. Now, what do we do now if there isn’t any drama? Can it be approached? That’s the challenge for me and I started to formulate the idea of banal aesthetics. What can we examine from that banality to make it more compelling? From the journalistic point of view, it is evident in every documentary. Present drama and there you have it. From all these banal photographs are the images of our everyday lives, so what’s the formula? Our lives probably did not rise and fall to a big extent and life on the road is pretty ordinary too. There is nothing that is exciting. The moment it becomes exciting, it falls under the category of journalistic photography. I’m not interested in that, I’m captivated by the banal happenings but how do I present them? That is what I’m trying to elaborate in Banal Aesthetics. What kind of aesthetics are we offering? So far, we knew that Henri Cartier-Bresson has already offered it, namely the ‘Decisive Moment’. From the ‘Decisive Moment’, we roughly learnt Bresson’s formula, which is a short moment in which different elements formed a meaningful pattern and we knew that it is potent. Therefore I’m toying with the elements from his photographs to obtain similar meaningful patterns that he felt. But, there needs to be another formula too. What if those elements are not clear? What if we can’t see those elements as a whole? How do we play with all this? That is the most intriguing challenge.

A

So what is your photography approach like? Do you already know the elements you are looking for or do you wait to capture one moment?

E

Probably a combination of both. Sometimes we can grasp the concept and create styles from photographers that we are familiar with such as Alex Webb of the ‘Under the Grudging Sun’. However, sometimes we can’t, so we just head out and try to capture something intuitively that reminding us of varying photographer’s style. Of course maybe ninety percent or more times, it won’t be as you expected. Nonetheless, as long as we have one percent of possibility, that is enough to make us go back and forth to the field and keep capturing pictures.

A

Is the one percent of possibility what you are searching for?

E

Maybe. I started the [book] project when the cost of films were still affordable. I was able to purchase cheap films that measured up to a hundred feet long, which I then cut by myself. The price probably fell below the market rate and even then it wasn’t that expensive to purchase . I could photograph more and also cut and develop the film myself before printing it. The budget was low as it was a personal project and took quite some time. Isn’t it fortunate now that everything is digital these days? These days, you just have to buy the camera and all that’s left to do is to photograph. Back then you had to calculate everything. I even had to include dating in my calculations. I would think, “I’m going on too many dates. Maybe I’ll skip it this week and spend my money on film, medicine, or something else.” It’s true that I’m pretty serious with my projects, which probably resulted in me not being very sociable. What I meant is I do not want socializing that would waste my working time. I much prefer working if I have to. If I wasn’t serious, all of these probably wouldn’t be possible.

A

How do you balance between the real and the surreal in your photos?

E

Sometimes realism is not enough to illustrate something. We need something above it. Why? Because what is realism? It’s an important question. Think about it this way: If I were to take a picture of you while you’re running, is the photo realistic? Do people really run like that? Maybe so. We would believe that this is how people look like when they run. But painters and sculptors in ancient times really knew how people look like when they’re running. The legs should be longer and bigger so that it leaves an impression of running. So they never created something that was proportional. But this isn’t necessarily true. If you measure the Selamat Datang or Irian Liberation monument, and re-make them according to human proportions, those monuments will not look right. The hands and feet would be too small. It means that the idea of proportionality and realism is not as what people imagine it to be.

People think that whatever is in a photographer is right. Because there is a dissonance between what we see and what our brain registers. “Oh right, that man is running.” But that’s only because our brain has already stored the image of a person running. But our eyes actually want to see bigger and longer legs so that they do not appear as being static. In describing the city, sometimes we need to use that kind of surrealism. Roughly right in surrealism that there are distortions too. Distortion is important to illustrate something that is caught by our senses. Because we are working on the right things — you could say something plain, flat. There is no drama. So it needs the application of other matters.

A

You once mentioned that you and Ayu [wife: Ayu Utami] are attracted to things that are not said. Where did that kind of mindset developed?

E

Yes, it’s just the mindset that I developed as a photographer. Photographers like to guess. For example, when we shoot, we see; “The two elements seem okay here. Will there be a third one?” You never know if a third or fourth element will appear. But I’ve trained myself to think that if I wait long enough, additional elements are bound to show up. The more I do this, the more trained I became, and the easier it becomes to notice the elements that are not immediately seen. Because often if you were to take a photo, it wold be up to that moment. There is a crowd. My friends in journalism feel the same way. For example at the 98′ demonstrations, the clashes were terrible — a lot of people got really beaten up. Those who are used to taking pictures of demonstrations would know what kinds of tensions would evolve into an actual fist fight. The photographers would know who would be involved in the conflict. It’s all part of the photographer’s job. I have been accustomed to guessing everything the moment I see something. “Ah, the person is going in that direction. If he goes in that direction, the composition will be good.” So the presence of a keen eye for reading our surroundings is really crucial. If a person has a crush on someone, I will know about it first. It’s certain. Even if a girl doesn’t know it yet, but I would know. I like to guess, and the outcome would mostly be right.

People talk a lot. Words are something that people offer so that others would believe them. But we can actually find out why a person would say what they are saying? Why would a person want us to believe that he or she is still a virgin? There are two possibilities: that person is a virgin, or that person is not. So which of the two is true? It can be easily seen from the small details that person reveals unintentionally. Once, Ayu received two hate letters that were written really poorly. But those letters had a really big role. At the time, we were still dating, so that we knew that the sender was someone we knew well. People who know a lot of information. There can’t be more than 20 people who knew us personally. It’s easy, right? We just need to know twenty people, and pay attention to them. Suddenly one of the twenty people told us that that person heard the rumor from a friend. That story was the only key Ayu and I need to know that that person was the who sent the letters. So what I want to say is that everyday we are surrounded by a lot of information. It’s up to us if we want to notice it or not. And if we want to make sense of it. Sometimes we just need one additional piece of information to put a bigger story together. Just to confirm it. Of course, the number of additional pieces of information vary depending on the context. It’s an interesting exercise because we can see the world in a different way. Using your imagination in this case is really fun. For example, we can try to figure out a person’s character just by looking at their shoes. What shoe was chosen and from what class. Roughly like that. Another shoe, another guess.

A

What is Ayu’s role in your work?

E

I am used to editing my work on my own. Always thinking that my work is the best. But that is where the danger lies. You will always need a second opinion in your work. Ayu has a keen perception towards photography. She can take pictures, and I believe she has a really good opinion about photography. Either way I am a practitioner, I have the rule of thumbs I abide to. It is not the case for Ayu. With her extensive knowledge and neutral stance, she can have an opinion which is much more valued. Sometimes we have different opinions, but we discuss it thoroughly.

A

What else would you like to explore?

E

I am currently in the middle of working on my next book. It still revolves around Jakarta but the theme is narrower. It is about the “public spheres.” In “Estetika Banal,” I included a lot of varying elements like the pro-democracy movements. In the next book, I will cover a tighter scope. Public spheres here exclude shopping malls. Malls have private owners; there are rules and regulations in malls. In public places, people do not know each other and there is diversity. So the potential for friction is higher. The height of civilization can be measured in public spaces. Because the importance of every layer of society is exposed there. You can see who holds power in society. If the lower income group is stronger, the richer class would be tighter.

Suppose a Ferrari makes its way to a slum area, colliding with a man pulling cart. Don’t think the cart-puller would make way so the Ferrari can pass. He wouldn’t. His eye would say “you force your way, and you will be in trouble,” this is authority owned by people in their own area. That is the height of civilization that I find interesting to uncover.

Documentation of cities have so much potential. They offer so many emotions and imageries to be captured. I’ll continue to document cities, and maybe explore different mediums. For my next book, I will start challenging myself with color photography after 20 years of using black and white film.