Political Research with Philips J. Vermonte

Muhammad Hilmi (H) talks to CSIS' Philips J. Vermonte (P).

M

What drew you to the field of political research?

P

I always had an interest in history and social studies, even though in highschool I majored in IPA (the sciences). To be honest, I had to take remedial classes after examinations (laughs). I was allowed to take IPC (mixed curriculum), and then majored in International Relations in UNPAD [Universitas Padjadjaran]. Like many new international relations students, we talked about subjects removed from our reality – The Soviet Union, Africa, etc – political science, in general, can feel far from what’s happening around you.

In the early 90s, student movements weren’t strong, unlike post-1998. In 1998, you would be considered strange if you weren’t in the student movement. In the early 90s it was the opposite – if you were part of one, you would be considered strange – it wasn’t the mainstream. It just so happened that I was friends with student activists, and was introduced through discussions to the subject of authoritarianism, etc, which made me become more interested in politics. The subject that felt removed, is real domestically, which inspired my interest – I began delving further into the subject. That is my initial interest in political science.

Cities such as Bandung, Yogyakarta, and Malang has a considerably long tradition of activism. During those years Yogyakarta had excellent student publications, Malang as well. A couple of friends and myself were inspired to start our own publication. We thought to ourselves, “why weren’t we, social politics students, writing?” – our arguments should be written. So that is why we started our own print, and after we began, we never stopped. Everything we discussed can be written, and I haven’t stopped since.

M

How did you become a part of CSIS?

P

I joined CSIS in 2001 after getting my masters degree in Australia. When I received my bachelors degree in 1996, though there was the July 27th PDI incident [a clash between two PDI factions, Megawati Soekarnoputri and the government backed Suryadi], a serious opposition against against the Suharto regime wasn’t too apparent.

There is a regular problem student activists face when they graduate – as a university student, they protest, and when they graduate they do not know where to find a job. I took a relaxed approach and worked whatever I can. I was working in an advertising agency, creating commercials for tv, radio, etc, but in the back of my mind there was this yearning to return academia and research – I actually planned to teach in UNPAD when I graduated, but there was this zero-growth policy where a job vacancy can only happen if somebody pensioned so I couldn’t do so.

I also wanted to become a journalist at the time and applied to ANTV, which had an excellent news department headed by H. Azkarmin Zaini, formerly of Tempo. They did the first live report, having the first satellite feed, about the Garuda-flight that crashed in Medan. I did multiple job interviews there, and when there was only one step-left, Indonesia was faced with the monetary crisis in which ANTV was affected badly, and station’s recruitment was discontinued.

During that time, Indosiar had just started its news department – which was run by Kompas journalists – and the same thing happened! (laughs). This time it was because Universitas Indonesia had a broadcasting department, and a MOU with Indosiar to recruit its graduate (laughs).

I tried once more with Majalah Umat, but on the day of the final interview, I was stuck with a client from my advertising-job, the traffic was bad, and arrived at the Majalah Umat office at 7 PM when I was supposed to be there at 5 PM. I could see the interviewers face was already very displeased and I knew I wouldn’t get the job (laughs).

I suppose I just wasn’t meant to be a journalist or teacher. I applied for a scholarship, and I was accepted, I guess that was my fate. I studied international relations in the political science department, returned to Indonesia, and was accepted in CSIS.

M

Could you tell us what CSIS does, exactly?

P

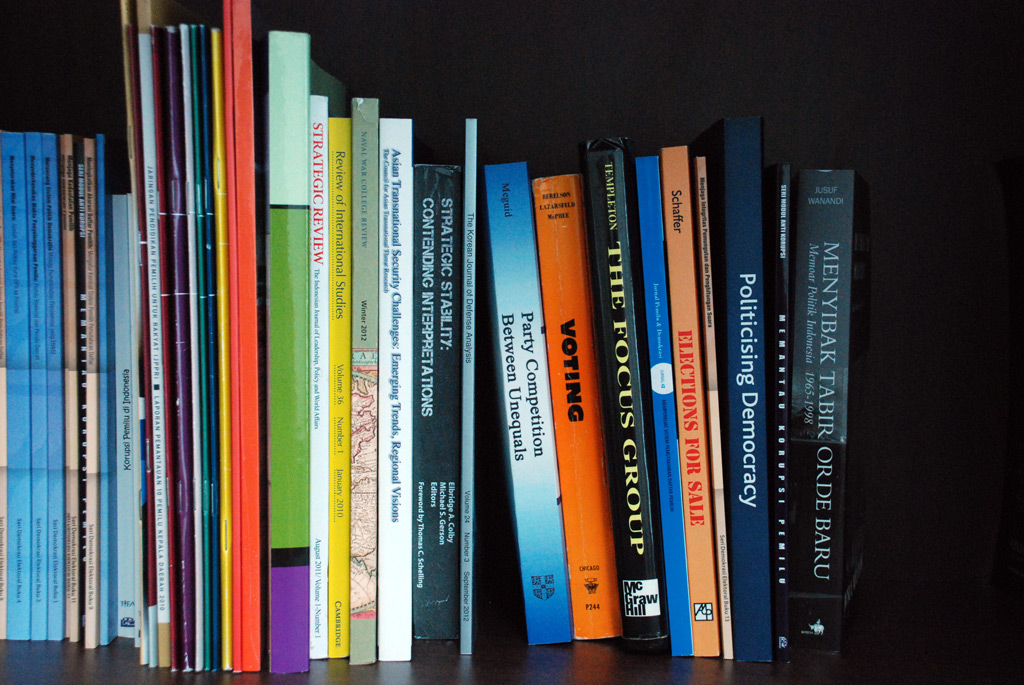

CSIS is a think tank established in 1971. It is a policy oriented institution, so it isn’t a purely academic. The organisation allows us to teach part-time, I myself have taught in Universitas Paramadina, and do research as well. The two main functions of CSIS are research and studies. We also have public seminars, book launches, discussions – like other organization. CSIS is focused on economy, political study, and international relations. CSIS also has published one of the oldest journal in Indonesia, in the Indonesian language is Jurnal Analisis, and in english is Indonesian Quarterly.

Who are the users? The content is, of course, for the general public, but because one of our focus is international studies, we make the effort for our ideas to reach institutions such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, etc. Same thing with politics, we have our networks and forums, political parties, etc.

M

How does the relationship between CSIS and ministries, forums, etc, work? Do they request a research from CSIS?

P

As Indonesia has become more democratic, there are now a number of research organization and think tanks. If, let’s say a government institution contacts CSIS for an opinion, it is very likely that they will contact other think tanks as well, creating a competition to propose a policy. There is always competition in recommendations, as it affects many parties’ interest.

After 1998, there are more competition, and that is a good thing because it will create an optimal collective research, or at least it should be that way. So perhaps there is a government institution who ask for our help, or even if they do not ask we send them our research and opinion – we advocate our work, of course. Whether they will use the information we gave them is up to them.

M

You mentioned that CSIS was sometimes viewed as the research center for Soeharto’s New Order. How did it transition into being independent?

P

The deciding factor is the CSIS’ commitment to research. Policies are linked to politics, but there are many organizations conducting politics without research – hence they do not have a long-term base. CSIS’ core-competency is research, not politics, meaning CSIS would continue with whoever in the government – it is essentially independent from the government. It is quite different from other organizations established to support a figure. When that figure is no longer in the public’s eye, those organizations will also disappear.

M

Are there any CSIS’ recommendation that is considered to be a milestone?

P

I can’t answer the question because policies are the result of recommendations from various organizations like CSIS, hence there can be multiple sources that influence a policy. CSIS itself hasn’t focused on getting accolades for our recommendations, this is an era where input can be from many sources, where the government or organization can create policies based on the best information available.

M

The 2014 Presidential Election very much brought the quick count, and its organizers (including CSIS), into the public view – particularly because of the confusion made by a couple of inconsistent results by a number of survey institutions. What are your thoughts on the subject?

P

That goes back to whether or not the organizers have a commitment to their research and recognize what the public say – an honest approach to reality. The problem with the 2014 election quick counts is this: a discussion on quick counts should be purely about science, methodology. Politics was brought into the discussion in this election, creating a grey area. For example, regarding funding, people would say “oh, you are funded by person A, then you’re partisan.” Funding shouldn’t affect the quick counts as long as the organization is dedicated to research and finding the honest result.

What resulted from that confusion, though, was a greater interest in quick counts – people wanted to know what quick counts are all about, and followed the news, which is wonderful. Indonesia is a democracy with direct elections, which means that we have an opportunity to understand what is in the minds of the Indonesian people, and we can do this effectively using statistics – we do not have to ask the 200 million who they will vote for, that is a census. With statistic, we can gather a sample to represent the population. The public is starting to understand that with scientific methods we can create an inference for a whole population.

Surveys are an interesting phenomenon as it didn’t start very long ago – around 2004. The public is learning to accept scientific methods conducted in politics, and the surveyors are also in the process of learning, as surveying is a relatively new activity here.

Quick counts should belong in the scientific context, in my opinion. The final decision will be decided by the election organizers. The function of quick counts are two-folds in most countries: firstly, it prevents manipulation of votes because with a scientific methodology we can reasonably assume what the results will be.

M

And the second reason?

P

Because the politicians want to know the results (laughs). It takes about 2 weeks for a manual count, and many things can happen in those two weeks, so it is better for them.

In my opinion, the General Elections Committee should adopt the quick count technology. Quick counts works like this, we have a 2000 election site sample, where we have a person working in each of them. They have a program that can send a number based on the election site’s recap of the votes to us, so we can count them in real-time. It wouldn’t be difficult to General Elections Committee to invest in this technology for the 500 thousand election sites. The head of each election site, accompanied by witnesses, can input the data, which can then be counted remotely by the General Elections Committee and can be uploaded on their website in real-time. The manual count should still be conducted, because if there were any problems with the quick count technology that could use it as a reference.

M

You are frequently interviewed and discussed by the media, and some even think you are a foreigner.

P

(laughs) that’s funny. When I first started working in CSIS in 2001, I wrote a piece for a newspaper, Kompas, and my name was out there. The founder of CSIS, the late Hadi Soesastro, received a phone call from the immigration department. The immigration officer said something like “CSIS now has foreigners working for them?”. Mr. Soesastro was, of course, confused. The officer then said “who is Phillips Vermonte?” and Mr. Soesastro laughed. I am Padangnese, and we often have funny names (laughs).

M

What are your thoughts on the 2014 elections? There was the volunteer phenomenon, etc, and you have written a piece about the early years of Indonesian democracy.

P

2014 was very interesting, especially because before the beginning of this year I believed the elections was going to be trite and have little public participation. I thought so because in 2012, Jokowi wasn’t a popular name yet, and I thought the candidates wouldn’t be different from the ones before – the names we see will be Prabowo, Megawati, Wiranto, etc. Then Jokowi entered the race, his name became more and more popular, and the generation change that I thought was going to happen in 2019 happened this year. This, I believe, has to do with the spirit of the times. Why? Because according to data, about 60 percent of Indonesians are aged 40 or below – we are a young generation. This young population wouldn’t match with the leader of old, who deal with problems using the old ways, thinking in the ways of the old – it just wouldn’t match with the spirit of today.

In 1998, a large part of this under-40 generation were in grade school, junior highschool, and highschool. What does this mean? They grew up and matured in a democracy and were surrounded by technology. Just look at the vote count, where the youth’s solution to the dispute was to create Kawal Pemilu. We must give credit to the General Election Committee for uploading the C-1 forms online, but without the youth’s understanding of information technology, open mindedness, advocating transparency, we wouldn’t have Kawal Pemilu. It is a new solution to an old problem, and it would be ironic if we had a leader of old.

We are lucky that Jokowi won the race. Jokowi is a new player, doesn’t have ties with the New Order, his track record is relatively clean – though I believe as citizens, we should always question our leaders – but what we do know is that Jokowi isn’t linked to crimes of the past such as human rights and corruption. Today he is relatively clean compared to the others.

Another interesting facet we can get from Jokowi winning the election is that he may have opened the doors that could end the feudal culture. Think about it, Jokowi started as an ordinary person, isn’t part of Soekarno’s family, but managed to get nominated by PDIP. Before him, if you didn’t have ties with the Soekarno family you wouldn’t manage to do this. We must give credit to Megawati who gave Jokowi the ticket. This can be a precedent for other parties. If you look at the political parties, they were started by people who want to become president – Wiranto created Hanura, Prabowo created Gerindra, President SBY created Demokrat. Megawati has shown that there are weaknesses in the political party oligarchy – the 2014 shows this oligarchy can end in Indonesia.

M

Regarding neutrality in your writing and research. How do you maintain neutrality when you are associated with Anies Baswedan and other people who are pro-Jokowi?

P

Neutrality and objectivity are two different things. During Jokowi’s campaign, I was not part of the team. I am close to Mr. Baswedan – I helped him during the Konvensi Demokrat – and then returned to my work in CSIS. As Anies Baswedan was invited to be a part of Jokowi’s team, Mr. Baswedan joined, not me. Also, as an Indonesian citizen, I have the right and duty to express my opinion on what I believe is right. What’s important is that I do not force my beliefs onto others – if there are individuals who do not consider what I do to be neutral, I have no problem with that.

Before the elections I have on multiple occasions say that the media should announce an endorsement of their candidates of choice so the public will know their position. That would be much better than Indonesian media who say they are neutral but are obviously not. They should clarify their position, so the readers will know, but continue to give editorial room for the candidates that they do not support as well.

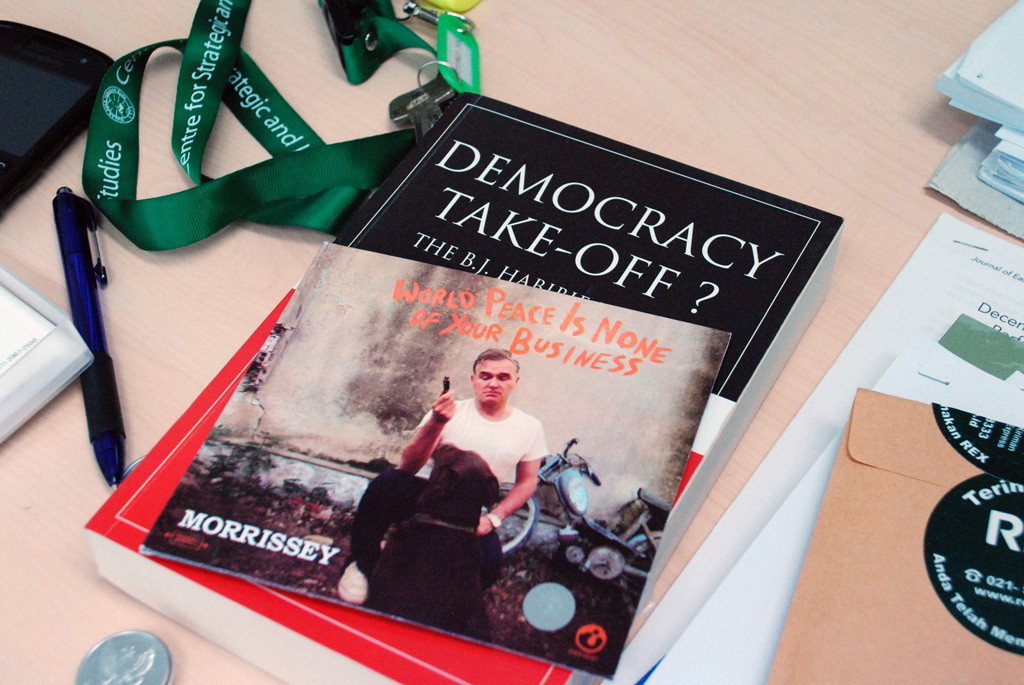

This happens all of the time in America – Rolling Stone, Fox News, New York Times, Washington Post – they all announce their positions, it’s quite normal. I believe this is good for the public and the media. This culture of endorsement could help create a mature media, one that can clarify their stance without sacrificing their objectivity, and people will appreciate that. We do not really have this culture in Indonesia – The Jakarta Post was the first to do so. I was quite surprised, and I thought it was very cool that they did.

Going back to the question of neutrality and objectivity, it’s okay for us to have different stances and opinions, what is important is whether or not we can argue in a civilized manner. If there was a Prabowo supporter who was being oppressed, I would defend him even though my views don’t agree with his – because we have to respect his right of expression.

M

You and Taufiq Rahman were responsible for starting the media Jakartabeat.net. Was that a way for you to channel your wish to become a journalist/writer?

P

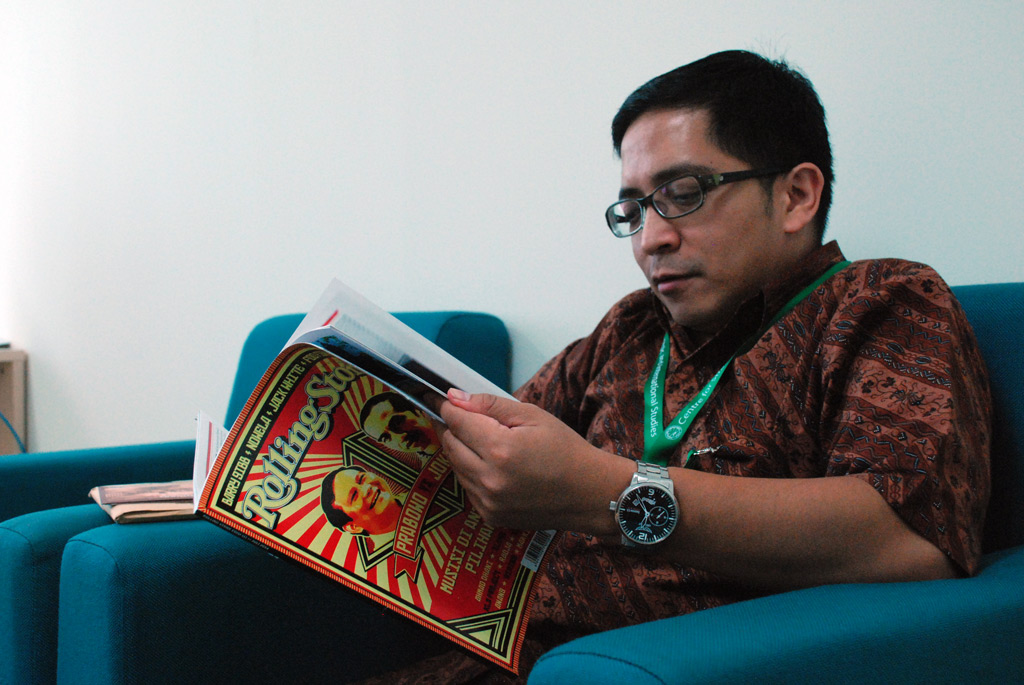

Maybe so (laughs). Me and Taufiq started Jakartabeat while we were stressed out with university (laughs). I used to buy a lot of magazines, particularly Rolling Stone Magazine America, which was my favorite. The magazine had very in depth interviews with political individuals, in depth essays, and of course they talked about music. Me and Taufiq were also heavily into collecting vinyl, where they had long liner notes talking about the history of the musician, music, etc – and thought it would be fun to make a similar type of media.

I think Taufiq spent more time in the music library than the department that had to do with his major (laughs).

I think what pushed me to make Jakartabeat was when I bought BB Kings “Live at Cook County Jail” record. Cook county was a, let’s just say, decrepit jail – it was bad, but BB King performed there. This performance caused a reformation in the jail, a realization that the prisoners were also human. Jakartabeat started talking about music and humanity partly because of this observation. We thought it would be wonderful to write about music with a narrative, not simply a report of a record release. We started with a blog, and then made it into a website. People said “who would read a website with long essays?” but people read it. This narrative-method of writing is what we wanted to push with Jakartabeat.

Perhaps this has to do with Indonesia’s literary culture. We are an oral culture – we can talk forever – but do not enjoy reading. It has gotten worse with social media. I think we should develop our literary culture, and we can do so by writing longer, contemplatively, with writings that are not too heavy.

M

Before Jakartabeat, the website/blog was called Berburu Vinyl. What are your thoughts on the popularity of vinyl in Indonesia, that it has become overrated, Taufiq Rahman even collects cassette now. Jakartabeat played a big role in popularizing vinyl.

P

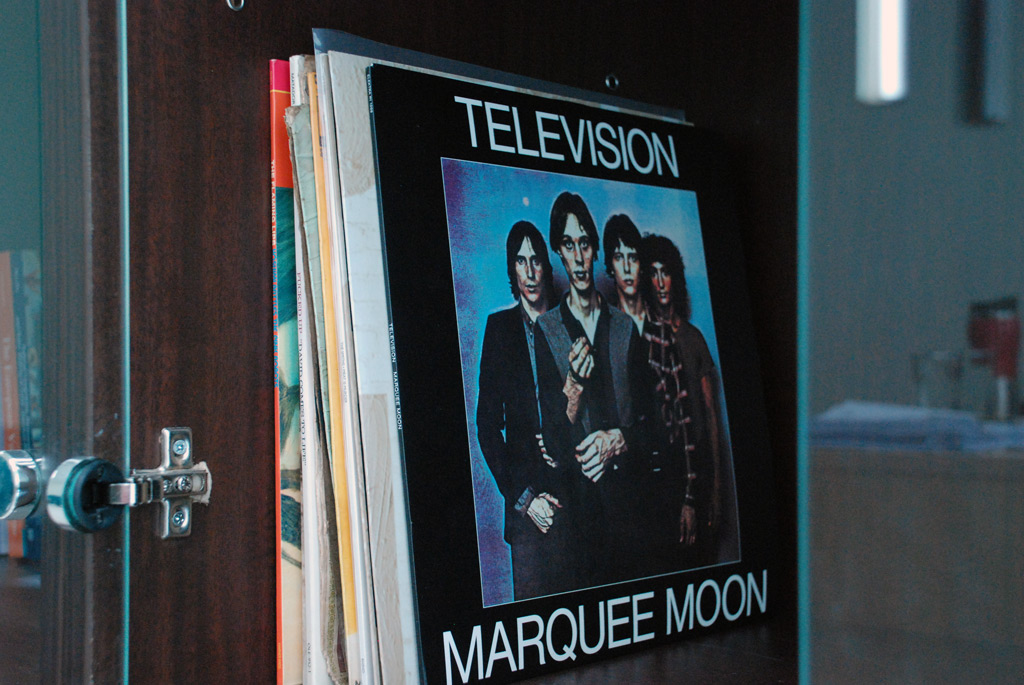

I’ve talked to Taufiq about this, I do not understand his shift to cassettes (laughs). Vinyl is a medium that lasts longer and delivers excellent sound. Physically it is the strongest and has the best quality of sound, cassettes are the worst in both aspects (laughs). Taufiq’s ideology is anti-mainstream, if it’s mainstream he will leave it (laughs). I got into vinyl because I wanted to collect Rolling Stone Magazine’s 500 greatest albums. If these albums have been dubbed the greatest, then I must collect and preserve the artefacts. If the mediums were cassettes, then they wouldn’t last long – same thing with CDs.

If Jakartbeat was responsible for the popularizing vinyl, then I say thank you. I don’t think there is a problem with people enjoying music through different mediums. If everybody collect vinyl, or if it isn’t cool to collect vinyl anymore – these things don’t matter to me. To be honest, not everything sounds best on vinyl. For example, in my opinion, I cannot tell the difference in sound between a metal album released on CD or vinyl. Vinyl is a good medium to hear textures, multi-instruments, so we are able to hear the details of the music. If you listened to Metallica’s Master of Puppets on CD and vinyl you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference, but if you listened to Metallica’s Orion, it would sound better on vinyl.