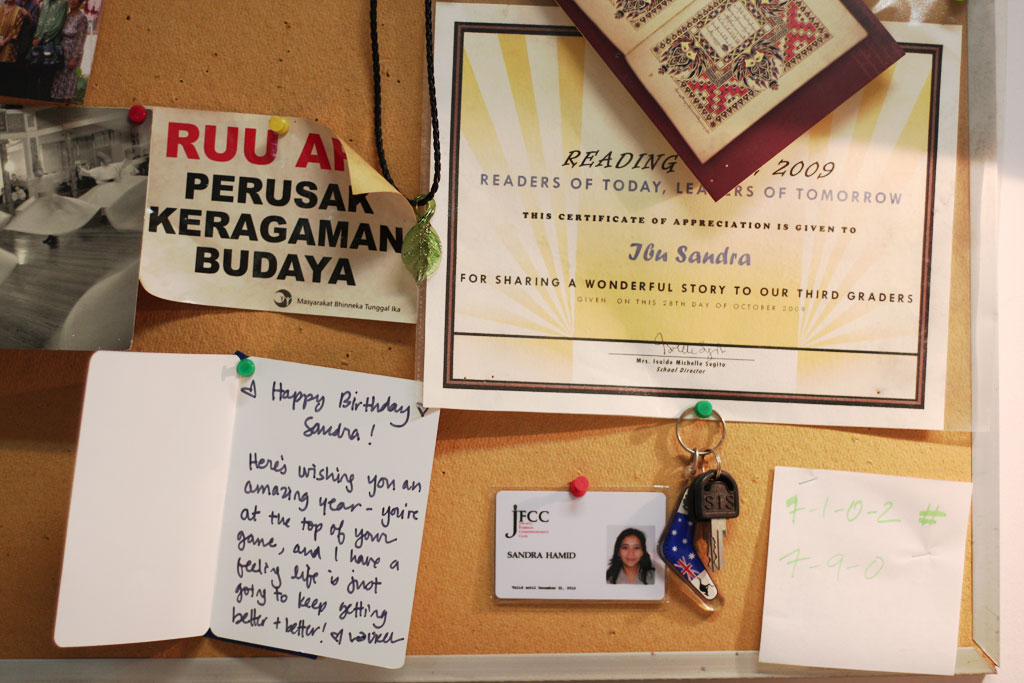

A Perspective on Indonesia with Dr. Sandra Hamid

Whiteboard Journal (W) talks to The Asia Foundation's Dr. Sandra Hamid (S)

W

You graduated from Universitas Indonesia with a degree in Business and Management and ended up working in politics. How did this happen? It seems like such a departure from what you studied.

S

Business has never been my first choice in University. My first choice was actually political science and actually did really well in it, but there was a moment where my heart was broken looking at Indonesia at the time. I had a political science professor that announced to the class “you better pass this exam because apparently I’ve been reported for teaching something I was not supposed to be teaching.” – this is during Soeharto time.

I was so angry and walked aimlessly contemplating the situation because I really wanted to do political science, but I felt so angry at the system. What kind of place is this that it cannot appreciate thinking?

I was 18 at the time and finally decided “forget it, I’m just going to do business.” That was my major but my heart was always in the arts and politics. Taking business administration was also the quickest way to graduate — I wanted to move on from this stupid college thing as fast as possible.

W

When did your interest in politics begin? Was it in school?

S

I think it started way earlier than that. Our family has always been actively discussing politics – the dining room was the place where we always talked about it, among other things. So it really started at home.

Also, growing up I was very fortunate to have a huge house and it became a place where my siblings’ friends and my friends would gather. My parents believed that it’s better to have people coming to the house rather than having their kids go out so people would gather at our home and I was exposed to many things, good or bad (laughs).

It was easier to discuss politics and take a side during the Soeharto era, because it was almost black and white – especially toward the end of his rule. You’d be crazy to be on the other side (laughs). When you’re young you want to be on the right side and you felt that you could do something.

W

After you graduated you worked for Periplus as a writer?

S

After graduating I tried to be true to business – working in Bali with an amazing designer, Linda Garland. There was then an opening in the Bali Hyatt I thought that it was a good combination of working in the corporate world and still living in Bali, so I took it… but I just wasn’t good at it (laughs). The hotel business is really about making people stay in the hotel, and in my perspective I told them “go! go!” (laughs). I was interested in culture and wanted people to experience the place [Bali].

My heart wasn’t in it, and Eric Oey, the founder of Periplus, was looking to make his own publication at the time and the first book he wanted to publish was a guidebook – specifically a Bali guidebook. I was offered the job and took it because it was cool. After the project Eric offered me to do a Java guidebook and Sumatra guidebook.

I am not trying to be biased, but I think the Periplus guidebook was one of the best guidebooks available. Eric Oey was an academic that is also a businessman and he studied about Indonesia in Berkeley, so he had the best academics contribute their knowledge on Batik, Borobudur, and so on.

W

How did this transition from working in business to being a journalist in Tempo happen?

S

I was able to work in Tempo because at the time the magazine wanted to make a special edition on Bali for a “Visit Indonesia” year, which was some time in 1991 or 1992. A friend recommended me because I have been living in Bali researching and writing. He recommended me and I worked with Tempo as a freelance writer.

Then, as luck would have it, they offered me to join them. They first asked me to join their Bali branch, but I didn’t have a background in journalism. My friend Amir Sidharta gave me a great advice, that if I didn’t have a background in journalism I better work in their head office in Jakarta because I will get a lot of mentoring there. That is basically how I started working in Tempo as a really lowly reporter (laughs) – I was really green.

W

Would you say that working for Tempo gave you the ability to channel your interest in politics?

S

Yes, absolutely.

W

What were important, I guess, memorable moments you experienced when you worked for the publication?

S

My first important assignment – one that really helped me grow was working in East Timor [in the early 90s].

W

That’s a very big deal!

S

That was a huge deal. I was assigned to follow this United Nations Rapporteur and when I was there when Santa Cruz happened, and so that was a pivotal moment in my growing up – in my knowing about this country more and my resentment against violence.

Note: Santa Cruz refers to the Santa Cruz Massacre, in which about 250 East Timorese pro-independence demonstrators were shot down by Indonesian soldiers at a Dili cemetery called Santa Cruz on November 12, 1991.

At the time I was inexperienced, but later on in life I reflected on the events and saw how important all of these competing discourses of an event is and how it has real consequences in people’s lives. Also, when you’re in this type of situation you find out about your own fears. As a person from Jakarta, there were times in East Timor where I felt animosity towards me, and it was really scary.

What East Timor also taught me was how… Yes, the shooting was wrong — completely wrong, not to justify the killings but you also have to understand how these kinds of events can happen. Later on, for example, we found out that many of these Indonesian soldiers were unprepared.

East Timor was a sobering experience. I interviewed this young soldier who was about to return to Indonesia after his assignment. I asked him his opinion regarding some of the things happening to the military at the time, the tribunals and such, and he told me “I don’t know and I don’t want to know, all I want to do is go home, I’m happy to go home.”

In a report, this young man would just be a part of a big machine that kills, right? But at the end of the day is a person who just wanted to go home. This for me was a big epiphany. People are good, but sometimes they lack the situation that enables them to do good. Who enjoys killing?! I don’t believe a person killing without remorse is natural. You don’t become trigger-happy just like that – you’re not born that way.

I wholeheartedly believe that people are inherently good. That’s why people who are in the position of power have more responsibility to create a system that enables people to be good. People are susceptible to be conditioned to hate, sadly, but that is the truth.

Being a journalist opens your eyes as you get exposed to so many different things.

W

These epiphanies you experienced during your work in Tempo Magazine, would you say that it influenced what you wanted to do next?

S

I guess… I don’t know, I mean, I have never been the type of person who would plan things like that. After working in Tempo Magazine I went back to school to study anthropology and the sociology of tourism – a subject I was introduced to back when I was working on the Periplus Indonesia guide books.

While I did some fieldwork in Lombok, which back then was always described in publications as “Bali thirty years ago” and “see Bali as it was.” Studying Anthropology I wanted to break it down, I mean, it’s impossible for a place to stand still in time. So I went there to do some theoretical anthropology, but when I spoke to the locals in Lombok about tourism what they would tell me was about politics – about how the local population was being displaced because of tourism, local investors would buy land and sell it to a Jakarta investor at a higher price, and so on.

What ended up in my dissertation is about politics and marginalization. My main stories come from marginalized people, people who aspire to be part of Indonesia being developed. People want to be part of Indonesia, part of the country’s development, but this development just does not include them.

Is it related to my previous experiences? Perhaps. I believe it influenced me, but at the same time your interests can naturally guide you. I think it is a little bit of both.

W

You are now working In The Asia Foundation as the Country Representative for Indonesia. Could you tell us a little bit about this NGO, especially its Indonesia office?

S

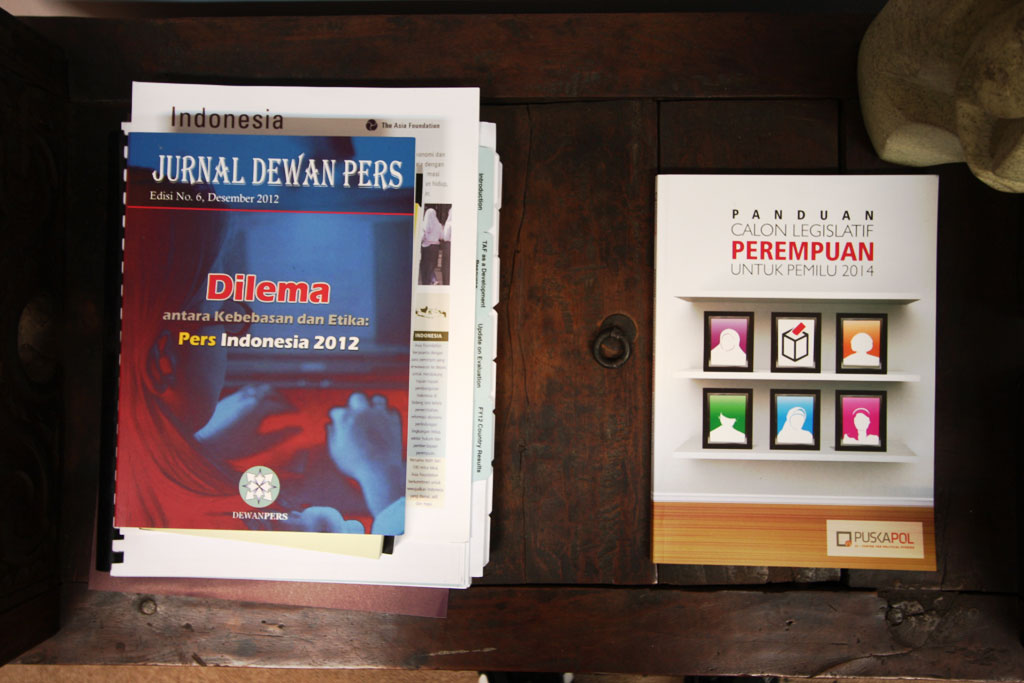

It is an American-based NGO, we are one of 18 offices in Asia and the main office is in San Francisco. There are major themes such as governance, gender and environment, but each country designs its own program. We at the Indonesian office do not have to work on those themes. At the end of the day those are important themes and we do work on some of them, but they do not drive our agenda.

What determines our workings on a certain issue are two factors. One is whether or not we can find a donor, because Asia Foundation is a purely donor-funded organization – we do not get endowments. So what we do depends on whether or not we can convince a donor to give us support in doing a particular work. Two, and it relates directly to Asia Foundation being donor-funded, we have to work on things that are really needed on the ground, not a program that is cooked up somewhere.

Everything is designed from the bottom-up. Our donors are based in Indonesia, we have worked with AusAid, USAID, Denmark, Norway, UK, and they are all based here. In other words, they know Indonesia very well and understand the situation here.

I love working here because we really have the room to design work that we, as an organization, think Indonesia needs.

W

What are some of the major programs Asia Foundation is working on for Indonesia?

S

I guess the spirit of what we do is promoting good governance in the different arenas. One of those arenas is gender and women empowerment. Our program on gender promotes civic participation – women participation – in being able to be actively involved in politics. Also in the gender theme is allowing women to tap into state resources. Budget is decided politically, and because women have little access towards the process of decision-making, be it in the village or city level, their interests are being marginalized – education, health care, credits for women, ownership rights for women, and others. So the programs concern women’s rights issue but also on the level of government, helping them to be part of the discourse.

We work on environmental issues, gender, economic governance, but they are all anchored in governance and government regulations to provide better services for communities.

W

Asia Foundation is addressing these issues on a long-term scale?

S

Yes, since we are a donor-funded organization, which usually isn’t long term -about 3 to 5 years, the question is how do we create sustainability. We always work with local organizations by providing grants and technical capacity building, which addresses the issue of sustainability. We provide the local organizations the assistance of our experts – quality control, research, data analysis, and so on.

We provide this assistance in technical capacity building, but the final product is the local organization’s because it is important for an Indonesian organization to be able to do it. After a certain amount of time they can now do it on their own – and that for us is an indication of success.

W

In an interview you did with the Lowy Institute for International Policy in 2012, you mentioned that religious intolerance in Indonesia is rising. Why do you believe this trend is happening?

S

I think it is really a combination of many different things. I believe that what we are experiencing is an increase in piety rather than conservatism and radicalization. People can conduct their faith more openly now and we actually benefit from that. There used to be a time when it was difficult to find a place to pray, now you pray virtually any time and anywhere, so there is an increase in piety in that way.

The rise of religious intolerance is a product of many factors, but what we know is there is a lack of law enforcement from the government, and that perpetuates people to continue with their negative behaviors.

To me, intolerance isn’t necessarily bad, because you are allowed to not like someone – that’s your right – what is bad is the violence that is acted upon that dislike. It is a matter of human rights and the role of the State. People have the right to believe what they believe in, and the State has an obligation to protect their citizens.

We [Asia Foundation] try to address this problem, but as a human rights issue rather than a religious issue.

W

In the same interview, you also discussed the election process in Indonesia and how it is difficult for voters to hold their elected officials accountable. I guess this is a simple question, but with the elections coming up it seems like an important issue to address. How do we hold our officials accountable?

S

This is the biggest problem we face in our democracy. It is very difficult for voters to associate a particular stance or issue with an official due to coalition parties. When you disagree with let’s say PKS and PPP parties when both are part of the Partai Demokrat coalition, how do you, as voters, make your decision in the next election? When Jakartans go to the ballots in the upcoming elections, all of the political parties involved have at some point made a coalition with each other.

There is no pattern in the permutation – as a voter one cannot say that “I will vote for a political party because their ideology is X” because the party with ideology X could easily form a coalition whose stance is the total opposite. Because of that it is very difficult to hold the elected officials from certain political parties accountable because they can always say “that is my coalition party’s policy, not mine.” Accountability becomes elusive for voters.

Elections, at the end of the day, is an event in which you either punish or reward your elected officials – you oust them from office, or you reinstall them because you trust them. The very essence of being able to do so is what is missing in our elections right now. Until we can do that Indonesia cannot have a very meaningful democracy.

Jokowi winning the Jakarta governorship was a breakthrough for Indonesian elections. He was in a limited coalition of two, PDIP and GERINDRA, which makes it easy for voters – we can hold him accountable in the next election. Meanwhile, his opposition, Fauzi Bowo, had the support of pretty much every other political party. If I was a politician the lesson I would have learned is that a big coalition doesn’t guarantee a victory because it is difficult to present a coherent message. Jokowi presented a small coalition, a clear message, and he won the elections.

W

Would you say the Jokowi-Basuki victory will influence future elections? Is it a game changer?

S

I think it should be a lesson to political parties. Will it be a lesson to political parties? That’s a different question (laughs).

W

A final set of questions. In this post-reformation era, where are we now? Has democracy succeeded? Do you have an optimistic view?

S

Of course it is an optimistic one. One should remember that service is not part of democracy, the promise of democracy isn’t one that guarantees citizens will be rich and so on. Democracy allows for people to have a say, to understand their role in the political processes.

If the question is “are we heading in the right direction? Are we better now?” I believe so because the participation of civil society is becoming increasingly meaningful. We’ve never had such a close relationship between civil society and the government.

On a voter’s level there is still a lot of work to be done. We still have a long way to go until the voters can find their elected officials accountable.

We also have a lot of work in pushing the media to be the motor that encourages accountability because media is one of the pillars of democracy. Indonesia’s media is quite amazing. Even if it is in the fault when opposing the government, Indonesian society will still defend it because of its history during the Soeharto era. The media has a social responsibility to communicate and relate information to civil society. My next big thing is working with the media to make sure they serve Indonesian citizens’ interests in seeking accountability of the political parties and officials.

As long as civil society is still very active then Indonesia is on the right track. For me, participation and the ability to influence public policy are very important parts of building a democracy, and we have never been stronger.