Part III: Under Earth

Part three of a six-part science fiction series by Khairani Barokka

Here is my list of songs to keep humming like a drill into the stress:

One: Widuri. Originally Bob Tutupoly (many covers).

Two: Hey Jude. The Beatles.

Three: The bread vendor’s song from my childhood, from back when he was just learning to avoid the becak drivers in flight, all of them in turn just learning to spin the wheels of air navigation and not get anyone killed. In addition to the sounds of hollowness, sludge, dirt squelching into nails, and mind-concocted fears in the fifteen weeks we’ve been trudging through this hole in the ground, this serrated street of endless dark, it’s a blessing that I can remember the taste of clean bread at all. The memory almost hurts the tongue.

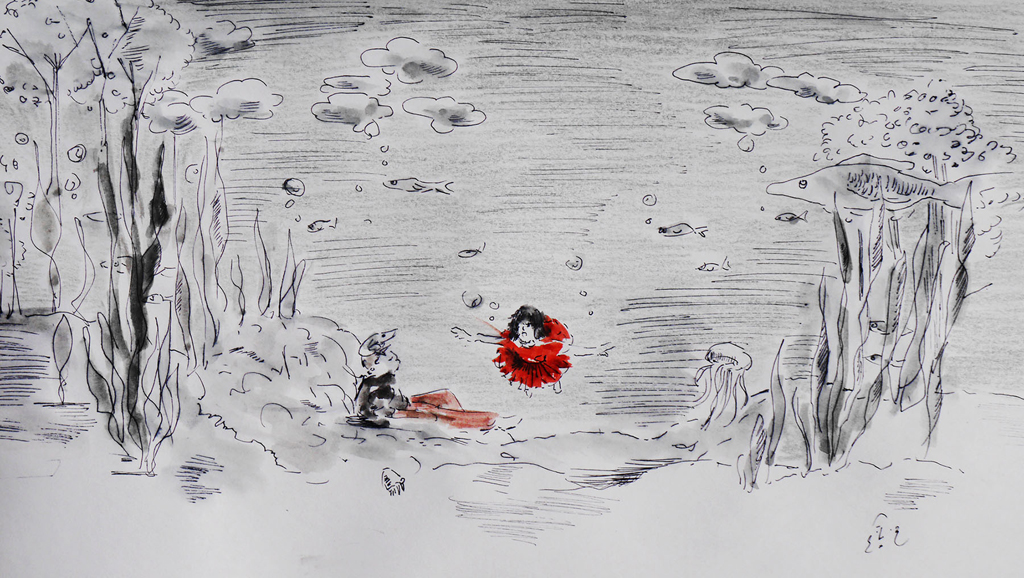

All of us embody desperation in generally similar ways, jerky kinetic forms in darkness, illuminated by the glow worms in netting that live for 200 years. Nonetheless, we harbor wholly disparate, intimate reasons for this catharsis in motion. Five dozen at a time, towards the promised sea, and even-more-rapturous promise of the under-ocean paddies, redemption, leaving anguished pasts on the surface of the earth, baking in sun and not to be thought of again.

My grandmother had told me how to find them, to find lunatic promise. She’d told me when I was a miniature thing how to contact the seeking tribe of refugees from the city, forgetting how unusual my memory was; years later, I brought back the imprint of her instructions to mind, proceeded with a scavenger hunt for the way out of slow death—our would-be murder by chemical inhalation, finding deformed chicken in our soup, selling trinkets worth nothing for a chance at more rice and waking up drowning in monsoon waves for half the goddamn year.

Quietly and away from my family, I played a delicate game of telephone through several people as peculiar as Jakarta can produce: a man with an iron rod through the front of the chest, selling kue putu by the side of the road, a vestige of violence even the headlines fear to drudge through; the wife of a diplomat stationed abroad who sent a lookalike from Banten to act in her likeness by his side, while she dresses in three-piece suits in Menteng and chortles at being “muka dua–saya bantu gerakan ini, kamu maafin ya, kalau saya suka cerutu Kuba?” She was in fact smoking a cigar I could only imagine was from there, or why bring it up? And a 12-year-old girl, raised in the ruins beneath Manggarai busway station, who read Emile Zola and Tan Malaka and very old copies of Hai magazine, and quoted them all and many more at random intervals before showing me the next step. The next person, the next discretion, the next secret, and then I was at an underground tunnel with these strangers and these living lights, the glow worms, we were on our way and I had left my grandmother a note I always jolt awake to the thought of.

Apparently my grandfather loved the song “Widuri”. Particularly the Broery Marantika version (he loved as well keroncong, and local stadium-rock of the afro-ed and long-haired variety). This anxiety, sludge-wracked, of eating carbohydrates we wince to taste and can barely see in this dark below the earth, of time and shadowy vision chipping at sanity’s facade, lulled slightly by this melody of karaokes past. Then I picture my grandmother’s face going dark as she realizes where I’ve burrowed into, knowing my departure flew in the face of her certainty that few survived the journey. The haze of my grandfather’s cigarette voice turns into his surviving wife’s regret, at telling me a fairytale as a child because she simply wanted to believe. In my mind, her face goes dark, thinking I will die in a place like this.

Who will wrestle smokestacks to the ground and pour honey into the water supply because some Muslim forebears said it would heal? What colour sarung is my grandmother wearing where I left her, looking up at the sky after her afternoon tea, where it wheezes vermillion gas into the lungs of the city?

The rows of the trudging in front tell us again, and again: there is a shimmering opening of sea at the end of this, ready for us to wear our suits of plant matter in. Helmets breathing oxygen into our lungs and chambers protecting our bones from crushing under many kilometers of blue, and there is no doubt that we will simply try for this liquid that feeds our thirst. There is no question of stopping, turning or longing for anything else but the sea.

Read the other parts here:

Part I

Part II

Part IV

Part V

Part VI